My first significant encounter with African literature and the people who write and live it was in 2007. I had read books set in Africa, sure, and even books set in Africa and written by Africans, but they were just books. They were interesting. They didn’t really mean anything to me.

But in 2007 I was put in charge of the annual literary festival held by our university here in Southeastern Ohio, a cheery three day affair of readings, lectures, and dinners attended by faculty, eager graduate students, and hundreds of undergraduates compelled by their teachers and who occasionally looked up from their phones and heard something that interested them. Along with the usual luminaries—chairs of creative writing programs and poets whose work appeared in the New Yorker—we agreed to bring three writers sponsored by our African Studies program. It is no surprise that I did not know any of their names.

My usual strategy of making all arrangements bloodlessly by email did not quite work. On the American literary circuit, writers tend to respond quickly. Not so with these African writers. I was given a list of possible invitees by our faculty, a wish list of prominent African figures in the literary world, accompanied by a hearty “Good luck!” I searched the Internet, called publishing houses, developed contact information that I was assured was reasonably accurate. I sent off my invitations by email and waited. In most cases I was met with silence. I imagined, with my utter lack of imagination about places I had never seen, that their computers were subject to regular blackouts and service outages, the result of collapsing governments or sabotage by opposition parties. But probably they were just not as fixated on their email as most Americans are.

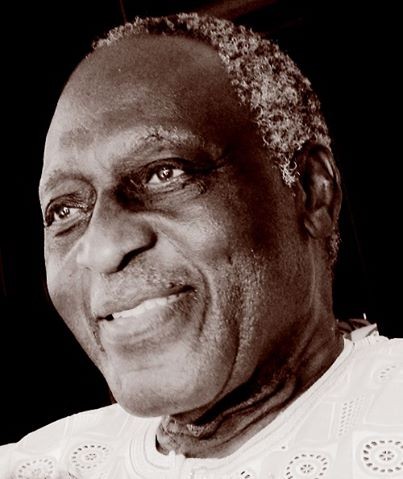

Kofi Awoonor was the easiest to locate; he was teaching in his native Ghana and I contacted him, after some fumbling emails to people with similar names, through his university. The arrangements proceeded smoothly, though his flight itinerary—from Accra by way of Europe and New York before finally landing in Ohio—was complex and looked exhausting. Nawal El Saadawi, the renowned Egyptian feminist, also agreed quickly but then dropped off the grid for several months; only a series of phone calls to Cairo (frantic on my end; unruffled on hers) finally assured me she would arrive in the United States in the time frame to which we had agreed.

For the third writer, the obstacles were more substantial. Chenjerai Hove had been living in exile from Zimbabwe for several years, after his house had been ransacked by thugs the Mugabe regime and his most recent manuscripts destroyed. I found him living in Stavanger, a fjord town on the Norwegian coast, with a small stipend courtesy of the local government. To obtain his travel visa, he had to undertake a series of eight-hour train rides to the American Embassy in Oslo, back to Stavanger, and back to Oslo again, at the cost of hundreds of dollars I could not find a way for the university to advance to him.

The writers arrived, much to my relief, on a sunny day in early May. The Appalachian hills around the campus were green and beautiful and the literary festival proceeded as expected. I tried to concentrate on the readings given by these writers and their American counterparts but mostly I buzzed around nervously and checked restaurant reservations.

What I did notice, more than their thoughts on literary craft or readings from their work, was the way that the presence of these African writers reshaped our usual audiences. When an American writer would finish reading, many of the typical undergraduates would file out, having fulfilled their obligation to their instructors. Then the African students and faculty would arrive, suddenly feeling like a critical mass on an otherwise overwhelmingly white campus. I do not think that all of them were great fans of literature. But they knew, in a way that I was only beginning to sense, what it had meant for these writers to pursue their work. All of them had spent time in prison, or been threatened with physical harm. All of them had come a long way to embody their work here in Ohio.

Literature is personal. On the first night, Hove read from his most recent novel. At one point he stopped abruptly, looked up, and pointed to the back of the auditorium. “That man understands,” Hove said. “He and I are from the same village!” The man half-stood and waved from a faraway row.

El Saadawi was demanding of me, her host—I was always getting her coffee, or tea, and the arrangement of chairs never quite suited her—but the crowd adored her. Women lined up to have their books signed by the writer who championed feminism and drew the ire of the Muslim Brotherhood. Awoonor was surrounded by Ghanaian graduate students wherever he walked. On the second evening, I escorted the visiting writers, American and African both, to the van that would take them back to the hotel. The man from Hove’s home village in Zimbabwe walked with us, beaming the entire way. When he waved goodbye, his smile was as wide as the minivan door. “That’s what joy looks like,” Ron Carlson, one of the other writers, told me. “We’re looking at joy right now.” Then the van door closed.

Once here it was difficult to go back. El Saadawi was receiving death threats in Cairo. We hastily arranged for her to adjunct a class over the summer, an intro to women’s literature class, and in late summer she received an appointment to a university in Atlanta. She was able to return to Egypt a couple of years later, in time to participate in the uprisings in Tahrir Square.

Hove’s needs were less urgent but for him, very real. Norway did not suit him very well. When I asked him what it was like for him in Northern white Europe, he looked at me with tired eyes. He applied and received a fellowship to an Ivy League university—another year with an office, he said, somewhere other than Zimbabwe.

Only Awoonor’s situation was more stable. He returned to Ghana on his flight as planned, resuming his duties at the university and continuing to travel in service of literature. I filed a volume of his selected poems on my shelf. I didn’t think of him much until recently.

Kofi Awoonor was killed in a Nairobi mall on September 21. He had come to Nairobi to participate in a literary festival, traveling the thousands of miles from one side of Africa to the other to teach a master class in poetry and talk about his time in a Ghanaian prison as a young dissident. In the two days that the festival proceeded—until it was jarred into silence by the nearby shootings—he was heard by hundreds of people and sat in conversation with writers from Africa, Europe, and America.

He was not a specific target of these men, who, like Awoonor, had arrived in the city just a couple of days earlier for their own purposes, to stage their own event; there is no evidence that they recognized him as they moved through the shopping mall located just a few minutes from the site of the festival itself; as they fired automatic weapons into the crowds, cornered people in grocery stores and executed them; or as they stopped occasionally to eat a candy bar or to make a phone call. They shot him, and he died next to his cup of coffee, and he didn’t mean anything to them.