I recently ran across an article in The Onion titled, “Nine Things Introverts Do All The Time.” It starts off innocently enough with some harmless long-lens photography and emphatic fan-letter-writing, but soon spins it into a dark, sociopathic narrative of stalking and abduction that ends in a fiery crescendo of homicide and regret! (Spoiler Alert, Introverts: We kill a beloved celebrity with our obsessive and apparently, flammable, love.) If you missed, click HERE.

Now I hope it goes without saying I take no issue with The Onion. (I seek them out regularly and I know what to expect!) But this piece made me wonder if we’re still a society that secretly considers introverts to be oddballs, outsiders, or in someway inferior to our extroverted counterparts—perhaps less socially developed or evolved.

My sense is that the problem lies in muddled terminology. According to psychologist Charles R. Martin, author of Looking at Type, the main distinguishing factor between introverts and extroverts lies in questions of energy: where do you feel the most energized, focused and restored? Introverts tend to be most engaged with the thoughts and ideas of their inner selves, whereas extroverts are more interested in their external interactions with others. Beyond this definition lies some common misconceptions, for example, a pervasive belief that shyness and introversion are one in the same. (Martin says that shyness deals more with a fear of social judgment – which is not a characterizing factor in introversion.)

In the past, I’ve found these errors of terminology to be common. When someone is anti-social, passive, humorless, or awkward, they are pegged as an introvert. On the flipside, a person who is warm, energetic, confident or well-spoken is deemed an extrovert. I remember during my Senior year of college, I took one of those personality tests intended to guide students to their ideal career fields. My results: INFJ – with the “I” indicating introversion. When I shared my results with some friends, one of them replied, “You can’t be an introvert. You tell such funny stories!” The others nodded in agreement. I don’t recall how I responded, but I think about her comment ALL the time.

“You can’t be an introvert. —–> You tell such funny stories.”

The logic still confuses me. Perhaps she was referring to the fact that the stories were sometimes told before a group, or that I seemed especially animated in the telling. I don’t know… but somehow, with just a passing comment, the ability to tell a good story about a chili dog eating contest was directly attributed to extroversion.

Have these labels become a lazy catch-all—introversion for the negative character traits linked with difficult human interactions, and extroversion with the positive, pleasant and entertaining? And as a result, is introversion being suppressed and disparaged? Perhaps people are relying too heavily on these two terms to categorize an array of personality traits that may be wholly unrelated.

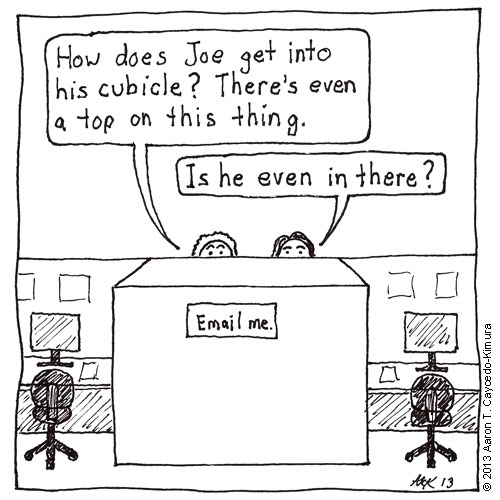

While researching this topic, I came across a very compelling TED Talk by Susan Cain, the author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. Her research states that teachers often believe the ideal student is extroverted, that introverts are frequently passed over for corporate leadership roles, and that in accordance with these beliefs, the American workplace is quickly evolving into an interactive space for sociable group-think. But in response, she highlights the value of independent quiet-time and challenges the notion that creativity and innovation alway come from such gregarious places. Instead, Cain asserts that for many, “solitude is a crucial ingredient to creativity” and that some of our greatest world leaders, inventors, and artists did their very best thinking and working when left completely alone.

While researching this topic, I came across a very compelling TED Talk by Susan Cain, the author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. Her research states that teachers often believe the ideal student is extroverted, that introverts are frequently passed over for corporate leadership roles, and that in accordance with these beliefs, the American workplace is quickly evolving into an interactive space for sociable group-think. But in response, she highlights the value of independent quiet-time and challenges the notion that creativity and innovation alway come from such gregarious places. Instead, Cain asserts that for many, “solitude is a crucial ingredient to creativity” and that some of our greatest world leaders, inventors, and artists did their very best thinking and working when left completely alone.

As a writer, I agree that long, uninterrupted periods of concentration and isolation are fundamental to my creative work (and I think the introverted tendencies of writers make themselves apparent through some of literatures most memorable characters: Mr. Darcy, Clarissa Dalloway, Swede Levov, Sula Peace, Ishmael, the enigmatic Jay Gatsby—all of them exhibit strong, habitual streaks of introversion and rich inner lives.) I acknowledge that workshopping, editing, and revising are often highly collaborative and useful parts of the writing process as well, but without the initial period of solitude, I suspect there’d be nothing worthwhile to collaborate about in the first place.

My intention is not to disparage extroversion. I think people should work, learn, and create in surroundings that feel most natural to them. My hope is that this same kind of consideration is extended to introverts by continuing to examine our own preconceptions of these social terms. By affording a less categorical and more nuanced understanding of introversion-extroversion, I think an inclusive model for leadership, productivity and creativity will result.

Oh, and the next time you’re strolling through your neighborhood and witness a house fire, think “irresponsible candle-owner” or “dummy who didn’t check the smoke detector batteries”… instead of introvert.