I’m often a little perplexed, when I read a review of a book, by the quotes that are pulled out as evidence of excellent prose. I don’t think great novels are necessarily composed of great prose, or that there’s a correlation between beautiful prose and the quality of a work of fiction. A really good, interesting novel will often let a little ugliness get into its words—to create a certain effect, to leave the reader with a certain sense of disorientation.

That’s from a Katie Kitamura interview with Jonathan Lee, up now on Guernica. I am not sure I agree. I resist the suggestion that great novels are composed of anything less than “great prose.” Those lines that might be pulled out of the text and floated in an atmosphere apart from the world of the novel–I admit that they’re just what I crave, in what I read, and in the words that I write. Nabokov: you’re out there, aren’t you, nodding your jowls in solemn accord? But that dismantling that Kitamura mentions, that gritty sense of defamiliarization she calls ugliness, sounds like the textural dissonance I admire in a piece of fiction, and that I am after in my own work. Elsewhere in the interview, Kitamura talks about breaking up her sentences, making rough patches in her work with jagged, rather than smooth prose. A rough and rusty nail that snags, startles, holds. A work too “smooth” becomes familiar, smooth to the point of numbness.

Novel sentences are a wider gage of sentence, a heartier, more capacious line, than story sentences, than essay sentences. I only half-believed a teacher who told me this years ago, until I started paying better attention to what worked and what didn’t in my own novel-in-progress, the force exerted upon the novel by its form.

I’ve been granted a good length of time to write a novel–a precious gift!–and the daily mechanics of the task are confounding and lonely, and new to me, so I am often unsure whether the gratifying moments of this messy job are real enough to keep and enjoy. But I am earnest, soothed by the triumphs of others, and devoted to study, so I began the summer by studying the shape of the competent 375-page novel. I read new ones, old ones, re-read some favorites, and restructured my own novel-in-tatters. By June, the pre-thunder humidity of my attic apartment melted my brains, made me delirious, and then angry, with the ungainly constructions I perceived in these books. I admit now that my anger was unfair. These books made me tired, but it wasn’t their fault. I obsessed over earmarks of the 375-page novel with unjust derision, a weird self-deprecation: The swift upbraiding of time. The clunky introductions of minor characters, minute and deliberate in a way unlike humans. The perfunctory meandering performed as if to distract from the through-line. Sentences heavy with exposition, retrospection, and summary.

I was confused: as a reader of novels, I had always loved the novel’s fatness and admired the elaborate architecture of its worlds. But last summer, perhaps because I was writing a novel, I suffered a crisis of faith. The form seemed excessive, cumbersome, leaden. I became angry, in the way of someone who suddenly realizes they are very hungry. But I did not want to preheat the oven, layer noodles, wait for the lasagna to be ready for dinner, heating the apartment in the meantime, losing my appetite. I wanted a popsicle. For its stickiness to run down my arm, and to savor its sweetness simply, tongue to skin. In retrospect, I think my delirious anger had less to do with the fiction I was reading than with my own panic over the task of ordering the chaos of my own messy novel. My dissatisfaction with my work, and with my contrived, bewildered dance with the trappings of the novel, mushroomed.

Poets talk a lot about taking a break from poetry, of taking a few months off from reading and writing verse to garden, read fat novels, or travel. A planned separation, advised for the health of the marriage. “I hate poetry!” they declare for a month, and then they’re back at it, honeymooning in a new notebook, refreshed. Fiction writers, on the other hand–in the bar, in the library–we just sound guilty all the time. “All I do is read! And drink! And sleep! And complain!” Or: “Just revising.” The days get away from all writers, but maybe novelists feel the guilt more acutely. Long works are stacked in perilous towers on our desks. Research is imperative, then a distraction, then a goiter; we keep renewing the heavy books of theory and obscure histories from the library, unsure of how we might put their turgid contents to use in our fictions. Our desperate notes stop making sense after a few weeks of neglect. Clutter and sorrow, shame and despair. Oh! And indulgence. More shame and despair, for the agony of melodrama. Never did my mother hit snooze seven times before leaving in the dark morning to open the doors of the homeless clinic where she worked as a nurse. She put on her sensible shoes and left the apartment, went to wait for the bus.

Do I hate the novel? Not just my shapeless pile, but All Novels? The thought pulsed in my brain like phosphorescence. I didn’t dare say it aloud.

I consoled myself by reading old interviews with Nabokov, faithfully driving my caravan to my favorite Russian aristocrat’s ardent place.

What I feel to be the real modern world is the world the artist creates, his own mirage, which becomes a new mir (“world” in Russian) by the very act of his shedding, as it were, the age he lives in. My mirage is produced in my private desert, an arid but ardent place, with the sign No Caravans Allowed on the trunk of a lone palm. No doubt, good minds exist whose caravans of general ideas lead somewhere — to curious bazaars, to photogenetic temples, but an independent novelist cannot derive much true benefit from tagging along.

I wrote an email, a less visionary refutation of the modern novel than Nabokov’s, to a poet-simpática:

I just want to read smart tiny paragraphs and poems written by the great ladies….Just–willful, no bullshit lil’ treatises… I’m trying to novel, but, girl, that shit is hard. Everything feels forced…more like formula than art…Or boring–like laying train-tracks. This has to go here, this has to go here, this is plotted on a grid, now the room is full of furniture, mark the dialogue, snooooze.

In my own work, I grew weary of indenting for dialogue, of determining where to stick my white space. Indignant about the polite fiction of introducing new characters by their relationships to other, known characters. Outraged by concepts of marketability. Betrayed and humiliated, already, by the hardcover dust-jackets on which I spied a dull exclamation such as “Engrossing!” Or the lazy shorthand of a ripe mango (“Exotic!”). Or an ugly shoe (“THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN BY A WOMAN”). A phrase along the lines of “As she had learned earlier,” seemed necessary for an instant, and the blood beat in my brain, hateful, tepid, and glum. Why are all my characters always rolling their eyes or taking naps? What a bunch of weak-willed saps! The chapter itself felt like a ugly, necessitated unit–the cheap white plastic bin that contains sweaters beneath a bed in the summertime, a 1990s bicycle helmet, a pair of boots impervious to sleet. I was sick of chapters, of working like a camera’s establishing shot at the beginning of each chapter. Bored by micro-denouement. What about Art with a capital A? Who needs this crap? I thought to myself. To hell with it!

What I desired, and what I continue to desire, is the willful shape. I desire not those words that do the work of building, of containing, of safeguarding, but those which Ukrainian-Brazilian bad girl writer Clarice Lispector desires when she writes, “I want to grab hold of the ‘is’ of the thing,” in Água Viva. I began to feel Lispector’s “perfect animal” of Near to the Wild Heart inside of me; I became a bad, bad girl.

“This is not a message of ideas that I am transmitting to you,” Lispector writes in Água Viva, “but an instinctive ecstasy of whatever is hidden in nature and that I foretell.” And: “My days are a single climax: I live on the edge.”

I didn’t abandon my novel, but I did put away, for a couple of months, the competent 375-page novels I had been reading. I set out to scramble my melted brains. I continued working on my novel, chapter by chapter, day by day, while feeding myself words imbued with the contrast fluid of essayists, poets, and the formally weird.

How charmed I was by Anne Carson’s blithe explanation for the format of her new novel-in-verse, Red Doc >, sequel to Autobiography of Red. A computer error, she explained in a recent New York Times interview.

Most of the text runs like a racing stripe down the center of the page, with a couple of inches of empty space on either side. This form was also a result of an accident with the computer. Carson hit a wrong button, and it made the margins go crazy. She found this instantly liberating. The sentences, with one click, went from prosaic to strange, and finally Carson understood — after years of frustration — how her book was actually supposed to work.

What freedom. Carson’s words are so astonishingly willful that they assemble like magnetized metal filings, no matter their shape on the page. But what horror that mislaid keystroke would have induced in me. Carson calls her husband, Currie, “The Randomizer,” and together, they use a random integer generator to reorder her work, staving away boredom. In the NY Times interview, Carson says of randomness: “It saves you a lot of worry. You know, all that thinking.”

Meanwhile, I ask myself: Dare I write a prologue? Can I jump into another point of view? How can I draw attention away from the retrospection? What is the goddamn narrative occasion? These large questions exerted their elephantine force on each tiny word I wrote. Am I so precious? Am I so afraid?

What I want to make is a collection of words which can only be pointed to. This desire does not set me apart from most of the other literary writers I know. We all want to make Art with a capital “A,” words too willful and saturated to be summarized.

I studied the way the slight, moving parts of Renata Adler’s Speedboat were scrambled, layered, and expertly snipped to form a fine-scaled collage. Slowly, I made my way back to longer works by novelists I loved. I watched Sebald jump into the heads of a series of characters, in the Antwerp train station, from the clutter of his East Anglia office, justifying his leaps in perspective with the will of the story. I returned to a book I had read and loved nine years earlier, long before I was plagued with anxiety about the form of the novel: How did Javier Marías get away with mentioning a family tragedy, as told by the protagonist, in the first pages of A Heart So White, and only revisiting the tragedy again, as a reveal to the protagonist, 200 pages later? I am not sure how Marías made the structurally atypical burial and retrieval of background information work in his novel, only that he did, and that the man hardly uses paragraphs, and that the pleasure of his sentences is so rich, that, as a reader, I do not care. I am certain that Terrence Malick (both the younger Malick of Days of Heaven and the older Malick of Tree of Life) does not lose sleep over character arcs, and does not feel the need to justify his locust swarms and galaxies, either. Susan Sontag does not tamp down essayistic impulses in her fiction, and introduces an entirely new consciousness at the very end of The Volcano Lover. How did she make these moves work in a novel? I’m inclined to say, thinking of Sontag’s terse, no-bullshit lil’ treatises on criticism, film, photography, and illness, by force of will.

In London, Sebald and Adler’s unwieldy auras gathering mass in my bag, I walked around the Institute of Contemporary Art’s “Keep Your Timber Limber” exhibit, admiring veiny cocks. No prologues, no transitions. My eyes roamed from the spell of cock to cock to unmitigated, unframed cock, each distinctly flaccid, throbbing, or wet, the necessary story in the lines. Pure is.

But my work is not in the painting of penises. Nor do I think that my current novel project is suited to the narrative-resistant shape of Lispector’s 120-page books, some of which are structured circularly, or, “as an inevitable encounter with nothingness,” as Rachel Kushner describes them in Bookforum. I think of topaz, the stone that obsessed Lispector and her work. Bright, uncompromising shards of prose that waste no time–how could I keep my novel sentences similarly intentional and sharp? As it reads now, messy and incomplete, the novel I have written is not built of aphorism, nor expertly collaged moments, nor is each line one that might be pulled out of the text to float in its own atmosphere, prismatic and light. But in fixing my gaze on these unusual shapes, enjoying and studying them, I did summon the will to shape my novel on my own terms, not on the terms of the form.

Mid-September, and summer is over: I’m back to the ornate university reading rooms and polite graduate libraries, wearing wool, and I have returned, more pious lover than bad girl when it comes to the novel (my own pile of pages, and the published beauties). I toil without glory, taking breaks to heat soup in dismal microwaves. I am less personally aggrieved by the shape of chapters. I return to sentences I hate, and I delete them. Then I rewrite them. My brains have relished their scrambling, and I am back to work, which, on most honest days, passes as tediously as it does willfully. Sometimes we need to trick ourselves into getting the work done. Our brains become over-reliant on habit, on the shapes we know. I don’t think it’s that we must choose between beauty and utilitarianism when writing novel sentences; perhaps we must contend with heavier elements, adjusting our temperature and speed accordingly. Out here in novel-space, nothing floats. We want the light, peerless gleam of gold, but we’re working with iron. Sometimes, though, I want gold filigree, and that’s all that will do.

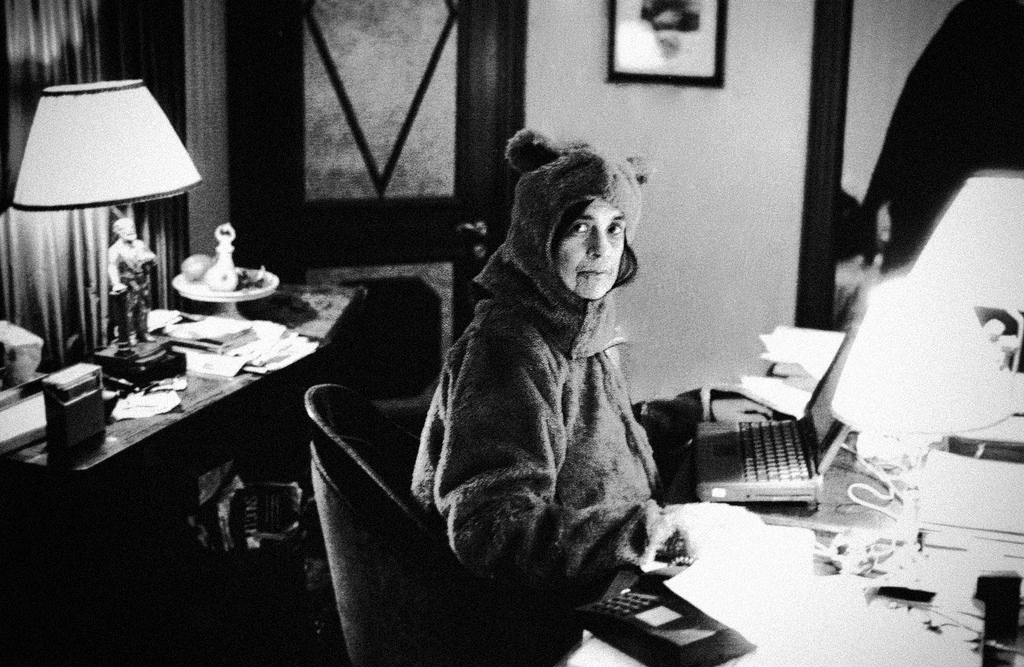

Photo Credits: Annie Leibovitz, Carl Mydans, Maureen Bissiliat, Terrence Malick