In the early seventies when I was a young assistant professor at Berkeley on my first teaching job out of graduate school, Thomas Flanagan got Seamus Heaney out there to teach for a year. Tom, the author of that great historical novel, The Year of the French, and his wife Jean were my guardian angels at the University. Seamus and I used to drink beer and talk poetry in the kitchen of his rather dismal rented flat in Berkeley. He had a highly refined sense of place, and as a refugee from the American South I must have seemed somewhat exotic to this visitor from Derry. Once, years later, at a dinner party at my house in Ann Arbor he got me to read aloud—because I have the accent—Cash’s list from Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying about how he made his mother’s coffin. There is nothing more Irish than a funeral, and today as I write these words on a sunny lawn in Southern California, the Irish poets will be gathering at the Church of the Sacred Heart in Donnybrook to mourn this great man, whose passing represents a loss to the world of poetry comparable to the death of Robert Lowell in 1977. The loss to Ireland is incalculable.

It was through Seamus Heaney that I learned some things about being Irish. When we were both teaching at Harvard in the early eighties, we met for lunch at the faculty club one St. Patrick’s Day. I had on a green necktie, everyone in town was wearing something green—but not Seamus. Wearing the green, being sentimental about the Ould Sod—this was what he called blather. The Old Norse root of the word means “to talk nonsense.” The mythical Paddy, the stage Irishman, was an expansive performer, and Heaney was fed up with that sort of thing. He had, on the contrary, what the poet Tom McCarthy has called “an elegant reticence.”

He came of age in County Derry during the Troubles, and Ireland to him was the land of the “neighbourly murder,” a cautious place, perilous to navigate, where “whatever you say, say nothing”—a hard-bitten place that has charmed the whole world with a smile and a song. Yet this was the same man who wrote: “Be advised, my passport’s green / No glass of ours was ever raised / To toast the Queen.” His emblem for the Irish was the haw berry—something like a crabapple, the fruit of the whitethorn tree. In his poem he re-imagines the berry as “the haw lantern,” which he characterizes as “crab of the thorn, a small light for small people, / wanting no more from them but that they keep / the wick of self-respect from dying out, / not having to blind them with illumination.” The lessons I learned from him about Irishness served me well when I went there to live for five years beginning in 2005.

When what he called “the phenomenon” catapulted him into a position of celebrity and he became “famous Seamus,” he accepted the attendant responsibility as a duty, a calling almost. To many people around the world, he personified Ireland. I am not suggesting that all the recognition was not a source of pride to him, but at times it could also be a burden. When I lived in Ireland I was singing the praises of my Senior travel pass that allowed me to take the train free anywhere in the country. He quietly and somewhat ruefully said that he couldn’t take public transportation anymore. He was recognized everywhere. In later years he drove what he called “a Mercedes automobile,” which he said Joseph Brodsky had convinced him to buy, even though he was slightly embarrassed about the ostentatiousness of it.

It has been said that “He was like a rock star who happened to be a poet”; but that paints a misleading picture. To put on airs, to indulge in any sort of flash behavior, would have been to violate the code by which he was raised. His father was a cattle dealer in County Derry, a prosperous man, what in Ireland is called “a strong farmer.” In his Paris Review interview he asserts that the Heaneys “were aristocrats, in the sense that they took for granted a code of behavior that was given and unspoken. . . . Either you were an initiate in the code or you weren’t.” Part of that code involved a sense of responsibility to the literary community. “No poet has a greater sense of noblesse oblige than Seamus Heaney,” Dennis O’Driscoll, gone now too, alas, wrote some years ago. “No poet is more willing to take his car into the dark, wet Irish night and lend his good name to the success of some exhibition, launch or reading. . . . He will stand stoically at a reception, radiating benignity, as if there was no other demand on his time . . . “

Whenever one came out with a new book, a handwritten letter would arrive in the mail giving a close and sympathetic reading and expression of support. He never forgot how hard and lonely a calling poetry was, and many writers could testify about the scrupulosity of his generosity. A kind word from him made that lonely calling a little more companionable. Of course there was a price to pay for all the recognition and responsibility. As his wife Marie once commented on Irish television, “There is no such thing as a free Nobel Prize.”

In 2006, after the old warrior had his stroke, I was asked to fill in for him at an event at the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin. Sven Birkerts, an old friend of Seamus’ from his Harvard years, was to give a talk, and I introduced him. Even though Seamus had not heretofore ventured out in public after the stroke, there he was that night in the audience. And after Sven’s talk Seamus rose unsteadily to his feet and made a few well-chosen remarks. He had taken to wearing an old brown felt hat, which his wife Marie said made him look just like his father. He was weaker, a bit uncertain as to his footing, but largely unaffected. When he came to write something about the stroke, which he always referred to as his “turn,” he characteristically framed the experience not in terms of his own suffering but in terms of the efforts of the friends who lifted him up and carried him to the hospital, just as, in the New Testament, a group of men had carried a paralyzed man to Jesus to be healed: “Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked / In their backs, the stretcher handles / Slippery with sweat. And no let up.” The Heaneys printed the poem that year on their Christmas card.

I’ve always felt that Seamus Heaney would have preferred not to be the poet of the Troubles, Irishman for the World. Like his friends Robert Lowell and Derek Walcott, he relished friendship, among people with whom he was able, as Lowell wrote in a completely different context, “to joke cruelly, seriously, and be himself.” For all his benignity, for all his capacity to be “the smiling public man,” in private he could be beautifully acerbic. But most of all, he had a huge gift for pleasure. One of my favorites of his in this vein is “Oysters,” which takes place in Moran’s on the Weir in County Galway, that lovely thatched cottage of a restaurant in Kilcolgan. I’d like to remember him there, in the second snug on the right, drinking a creamy dark pint and eating Galway Bay oysters:

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

We had driven to the coast

Through flowers and limestone

And there we were, toasting friendship,

Laying down a perfect memory

In the cool thatch and crockery.

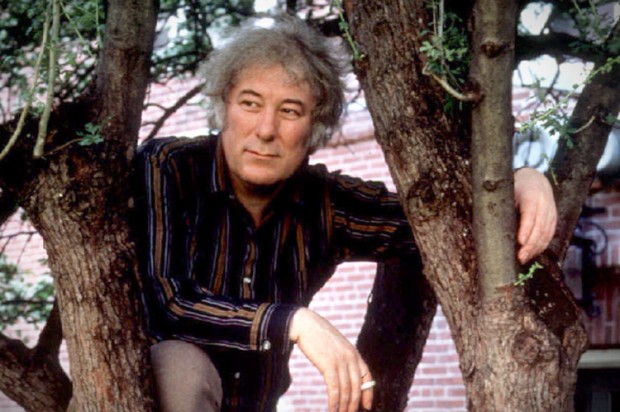

Photo credit: Reuters/Ho New