I read this Salon article about GenXers and mid-life crises which hones in on a few particulars of a generation’s anxiety about growing old. Author of the article, Sarah Scribner, citing economist and demographer Neil Howe, spoke of how the Boomer generation’s mid-life crisis was marked by a kind of claustrophobia over the constrictions of family and career, whereas with GenXers, the opposite fear prevails—an agoraphobia that paralyzes with seemingly infinite choices and options.

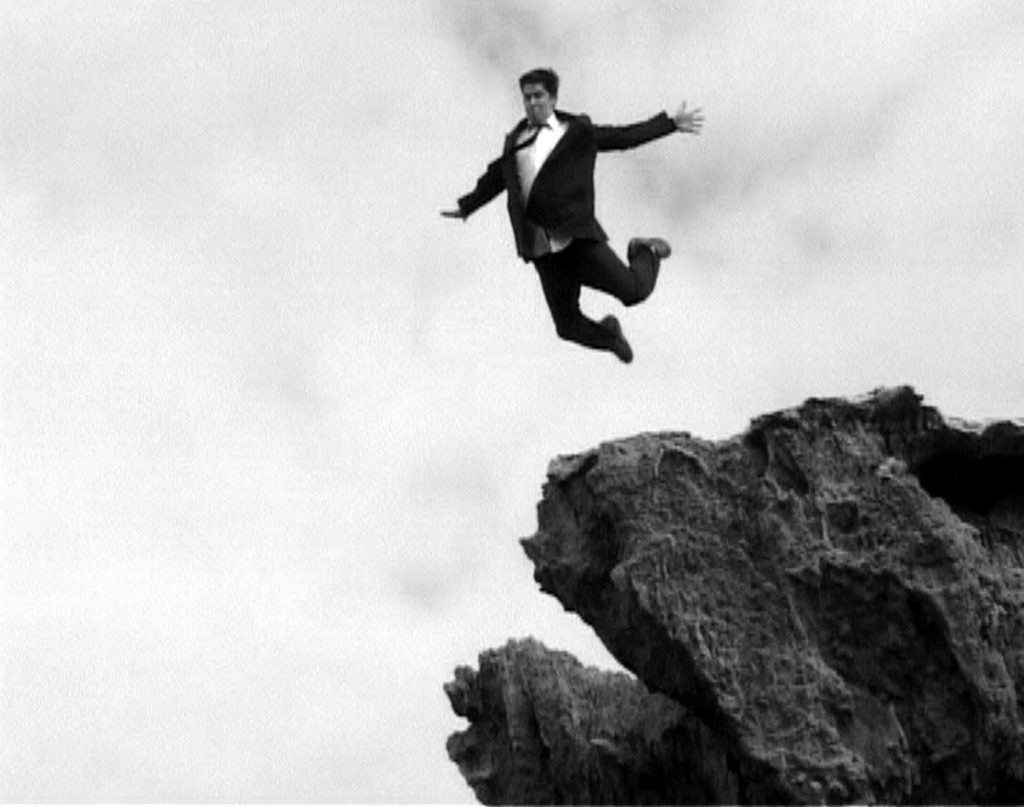

While I’ll refrain from characterizing an entire generation (I’ve always found that journalistic practice a little silly), I’d like to speak to what Scribner calls a ‘survivalist’ tendency in this demographic—that quality of enterprising restlessness, fashioned by economic crises, war, and two terms of a Bush presidency. Her insights resonated with me, and offered a point of entry for investigating something I’ve not yet been able to fully apprehend or contextualize—that is, the feeling that one is ever in transition, an existential vertigo—as though one were caught, mid-leap off a precipice, frozen in free-fall.

I know I won’t be settling down anytime soon, and it’s not for lack of want. Security in all its guises is such a basic need, that any appeals to freedom and independence, heedless of the security which affords them both, strike me as dishonest. The omnipresence of debt in my life, and in the lives of my friends, looms so large as to render most accomplishments miniscule. Scribner’s article mentions this too, and notes its positive reversal in a new class of entrepreneurs who’ve forged mindful, environmentally- and socially-conscious ventures, out of this smallness. The proliferation of small presses and literary journals over the past decade is just one example, from my vantage. Simultaneously motivating and sabotaging these ventures is a sense of fleetingness, complexly inflected in our age by recession as much as technhology’s break-neck progress. It’s a burst-bubble obsolescence built into, not just our machines or our investments, but also in the material reality of our relationships—with others, and our own passions. On any given day, it can seem either an anxiety or an acuity, alternately clouding and training our vision. So, to each other we can say with resignation, we have no future together, and in the next breath claim, with equal fortitude, we are building a relentless now.

The article, which concluded with a call to civic action, led me into a discussion with my partner about cynicism, prompted by his fascination with cynicism’s cultural role, and how it relates to people’s derogatory use of the term ‘hipster’. I thought of how anytime I’ve used ‘hipster’, it functioned as a shorthand for inauthenticity. I’ve used it to describe anyone performing their uniqueness, and seeded in the term is my disdain for what I perceive to be the indulgences and consequences of this performance. I use it, too, to describe those who prefer mockery over satire (the former ungrounded by, or contemptuous of, social responsibility), and to criticize their—in my mind, unearned—cynicism. I’ll grant, this judgment itself is pretty damn smug. As though one actually earned, as opposed to eroded into, a cynicism! But if I can count one lesson in my own meandering towards middle age, it is learning to appreciate the difference between cynicism and outrage; I’ve learned to identify, among other emotional states, those which foster action, and those which hasten atrophy. True change is revolution, and you can’t be a revolutionary cynic.

Being on the generational cusp of GenX and Millennial (I’m often exasperatingly optimistic, but sort of embarrassed about it), I’ve learned to breathe more easily in freefall, though I continue to seek boughs and footholds along the way. Given my vocation, one of those places to rest and regain strength, is poetry. For the moment, my rudimentary competence for spreadsheets is prized over my expertise in sonnets, and, while I still believe only the least marketable form of language can be of greatest human value, I also understand how this belief contributes nothing to paying bills or the rent. And I’m ok with that. Since last year, among other things, Madness, Rack, and Honey, Mary Ruefle’s book of collected essays, has helped me be ok with that. These essays model and exemplify how poetry, its practice and consumption, offers new tracks of perception and thought. In “On Secrets,” she veers from describing an opera singer to write:

I used to think I wrote because there was something I wanted to say. Then I thought “I will continue to write because I have not yet said what I wanted to say”; but I know now I continue to write because I have not yet heard what I have been listening to.

And later, in the same essay—

When you are walking down a city street and not paying much attention—perhaps you are downtrodden by some confusion—and come suddenly upon a rosebush blooming against a brick wall, you may be struck and awakened by the appearance of beauty. But the rose is not beautiful. You think the rose is beautiful and so you may also think, with sadness, that it will die. But the rose is not beauty. What is beauty is your ability to apprehend it.

—Which recalled for me one morning in Spring, texting a friend during a slow walk through my neighborhood. Torrential rains the days previous had bloomed everything nearly lurid, and I stopped to take a picture of a flower, impossibly pink and wet with dew. I sent it to him. “See?” he responded, “That’s better than Poetry!” I texted back, “Poetry saw this for me.”

And as much as I marvel at all the ways Ruefle demonstrates how poetry can function as perceptual enhancer, I’m even more grateful for how eloquently she places, illuminates, and sometimes deforms anxieties very similar to mine. In her essay, “On Fear,” she begins:

I suppose, as a poet, among my fears can be counted the deep-seated uneasiness surrounding the possibility that one day it will be revealed that I consecrated my life to an imbecility.

I’ve read this book and this particular essay several times, and Ruefle’s opening sentence here has never ceased to delight me. Its humor expresses how absurd and sublime any faith is, which has fearfulness as its prerequisite. The practice of poetry for me is always both a falling and finding a foothold. I return to this opening sentence, and I remain so delighted that I think it would make a marvelous epitaph for my headstone. Or perhaps, this slight modification— Here lies one who consecrated her life to an imbecility. The End.