Just like my first summer in the Midwest, this year it’s been relentlessly hot, surprisingly humid, and in my apartment, ever un-air conditioned. In July, I stripped my bed of its quilt and sheets, placed a fan in front of every window, almost cracked a tooth chewing ice. My cat has been nibbling on her Tender Vittles only infrequently, yawning often, and shedding continuously. She stretches out day and night on the cool tiles between the toilet and the shower. I’ve been eating mango popsicles for dinner.

This kind of heat—the kind that makes most movement absurd or impossible, robs you of your appetite, colors everything bright, wilts people and plants alike—is the subject of Florine Stettheimer’s 1919 painting titled, you guessed it, Heat. I first saw this painting three years ago in the New York Times, and even in miniature, I was struck by the saturated, edgy, unsettling—unsettling yet appealing—world of the painting. And since, on days like today (now, as I write, weather.com’s UV index warning reads “extreme”), I’ve thought of the piece often.

Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944) was born to wealthy parents in Rochester, New York, the fourth of five children. Her father left the family when the children were young, and the oldest children eventually married and moved away, but Florine and her sisters Carrie and Ettie lived together with their mother, Rosetta, until Rosetta’s death in 1935. Florine’s life in the arts was active—she was a painter, poet, patron, and designer—though her paintings remained largely unknown in her lifetime. (And they remained obscure for a good time after, too. Though Ettie declined her sister’s instructions to destroy the paintings that remained in the studio after Florine’s death; though Marcel Duchamp organized an exhibit of her work at the MOMA in 1946; though later artists such as Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns were interested in her life, her work, her collaboration with Gertrude Stein as costume and set designer for Four Saints in Three Acts, and her relationship with Duchamp; Florine’s reputation grew very slowly over the course of the 20th century. Many of the paintings Ettie donated to museums across the country spent years untouched in storage.) Alongside Carrie and Ettie, Florine hosted a famous salon that boasted such attendees as Marsden Hartley, Charles Demuth, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Adolph Bolm, Avery Hopwood, and others in the family’s New York City apartment. Compared to the artistic careers of some of her friends, however, Florine’s own was much more private. After the disappointment of her first and only single artist exhibition during her lifetime at M. Knoedler & Company in 1916 (mixed reviews, no painting sold), she kept her work close to home, showing paintings to friends and family out of her studio (which she decorated with cellophane curtains) and the family’s apartment. In the relative privacy of her social circle, her style morphed into the quirky, color saturated, symbol heavy, cartoony, kitsch style that makes her, in the eyes of contemporary viewers, so interesting.

Last week, on a quick visit to New York, I saw Heat, currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum, in person for the first time. And the painting, which shows Florine, her three sisters, her mother, and two cats paralyzed by the heat even as they celebrate Mother’s birthday, is just as oddball and theatrical and bright, as alluring and as slightly scary, as I’d hoped.

In the museum, I stood close to Heat, close enough that it occupied my field of vision, as close as I might stand to a person whose face I’m about to touch, whose breath I want to feel on my skin. I was reminded of my childhood visits to New Orleans, where my parents had lived years before. I remembered stepping off the airplane, out of all that chilled, recycled air and into deep summer in the deep south. I loved those first steps onto the jetway, the sudden and complete humidity that wrapped itself around me. At first, this wet heat would be wonderful, warm and comforting, soft and heavy, like a blanket. But then, as I followed the other travelers down the jetway, as I began to sweat though my shirt beneath my backpack, it became too much, too hot, too thick. My face and ears would redden. My denim cutoffs would grow sticky and bunch up between my legs. The heat became, in this space between the airplane and the airport, overwhelming.

When you look at Heat, take it in from top to bottom. Green, yellow, red: the painting leads you by the hand, and you descend into the heat together, from hot to hotter to hottest. See the green pool of water at the top of the painting, cool and dark. See the drooping limbs of the weeping willow. (Look at the tree again: it’s the upside-down torso of a man.) Rosetta manages to sit upright in her black sleeves and long skirt, stately and composed, dark and looming. The head of the family in her place at the top of the painting. The world of this picture is fantastical and curious and slightly eerie. It is, as Marsden Hartley said, “subject to special heats, special rays of light, special vapors.”

Move your eye down to the center of the painting. Find the two figures in armchairs, two of Florine’s three sisters. A swath of yellow paint across the center here to represent a stretch of dead grass. Unlike their mother, these two women, though upright, have lost their composure. They squirm in the heat. They’ve abandoned their knitting. I love that the sisters attempt to knit in the first place—imagine manipulating lengths of wool in this burnt and saturated world. Some days, the sun already feels so much like wool on the skin, hot and unbearable.

At the bottom of the painting, where the world turns red, the heat escalates and overwhelms: we find, sprawled across couches, above a red rug, two more of Rosetta’s daughters, so unlike her in their unabashed repose. They—and you—surrender to the heat. Find Florine at bottom right, dressed in white and pale rose as if her whole body were feverish. A black cat tugs on her limp hand. A fan useless in the other. One shoe off. She looks like Isadora Duncan, limbs soft and slender, barefoot. Her head droops to the side. Her sister on bottom left, in brighter pink, stretches her long arms, flushed and feline.

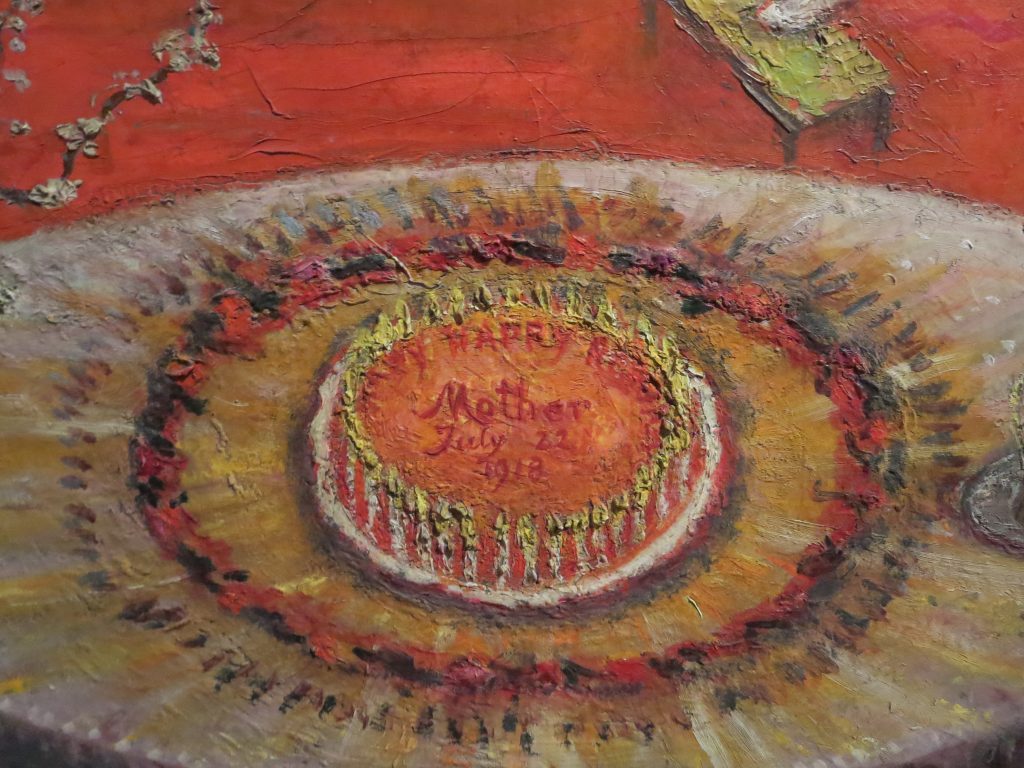

See the table and birthday cake at the painting’s bottom edge: this, I think, is Heat’s most mesmerizing and intoxicating image. The candles blaze, transforming the table into a wild red eye. I am drawn to this eye, which despite being at the bottom edge feels like the composition’s gravitational center. A sun. And the shallow landscape becomes scorched in its presence. The figures in the painting seem to orbit accordingly. Here, at this bright center, the premise of the painting—heat—escalates and intensifies, becoming for me appealing and frightening, illuminating and threatening.

I remember once, when I was a child, my mother took me into the steam room at her gym. I was terrified immediately—naked women with their eyes closed and heads back, the rumbling of the steam machine, the hot water in my eyes and mouth. I screamed, I think, and cried. And she had to carry me out, dry the tears, snot, and sweat off my face. I can manage steam rooms now, and saunas too, though what I love about them still makes me uneasy: the building intensity of the heat, the warmth that grows until I can’t remain a minute longer, until I need nothing more than dry, cool air. This is where Heat takes me.