With the help of some friends, I staged and photographed several moments of pause in Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. My actors, amateurs all, writers all, wore modern street clothes and occupied their roles in an intimate, dim, untraditional space, in this case, my attic apartment on the Old West Side of Ann Arbor, Michigan.

For just a moment, the audience of The Cherry Orchard observes a nervous man embrace a bookshelf like a lover. The life around Gayev is pauses, and the effect is like that of a musical fermata.

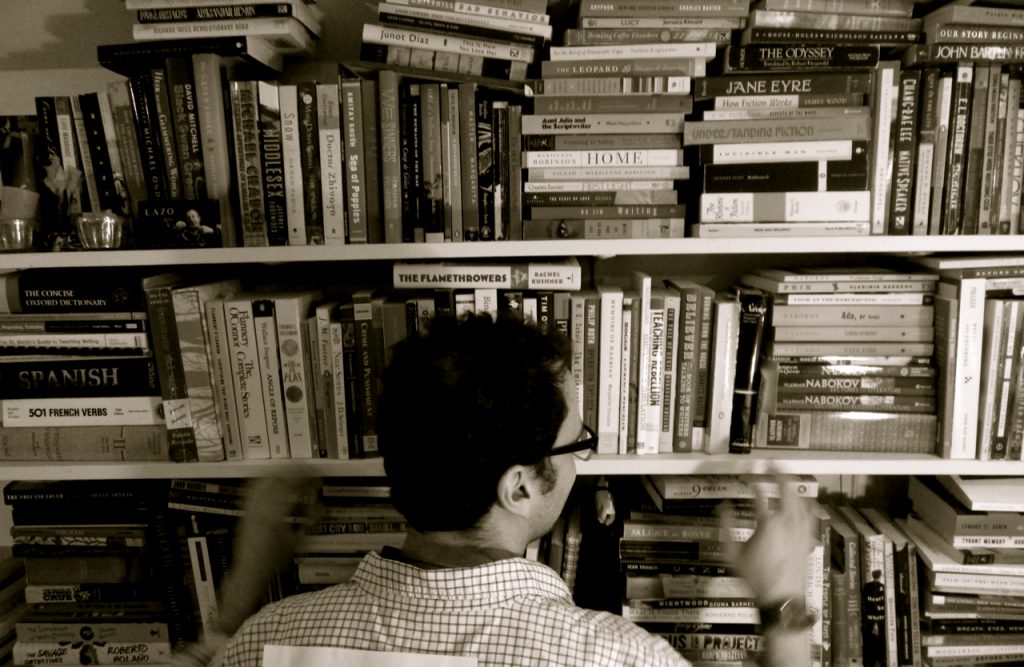

Gayev’s moment of quiet pause, during Act One of The Cherry Orchard, is staged by a close friend and fellow writer of fiction, Daniel DiStefano, currently at work on a novel about Sicilian immigrants in mid-century New York City. Hovering above DiStefano’s head in this photograph is The Leopard, Guisseppe di Lampedusa’s imagined history of his Sicilian prince great-grandfather, a seminal, instructive text for the living writer, when he is not playing the role of an amateur actor playing a fading Russian aristocrat. This amateur actor’s embrace is as sincere as Gayev’s, though compelled by different motives. Like Gayev, who says, just before caressing the bookshelf, “Of course it’s an inanimate object, any way you look at it, but still, it’s a…..well…..it’s a ……bookcase,” DiStefano loves the bookshelf he embraces with a passionate and principled force. He collects early editions of his favorite authors, and since the shelves of his apartment are full, he stacks volumes on the table beside his bed, on a high butcher-block table others might use for preparing food or dining, on the cushions of his couch.

Gayev, of course, is overcome by another set of forces. For Gayev, the bookshelf is precious enough to embrace not because of the literary value of the individual texts it contains, but because of the object’s venerable age, its “ideals of goodness and justice,” and of course, because of his own pronounced eccentricity. For Gayev, the terror of loss looms with the passage of time. Let us celebrate the past by honoring a wooden case of shelves with an extravagant birthday party; let us hold onto the past. The pause Gayev seeks is longer than the one that Chekhov permits him. If only Gayev could stop time, return to the opulence of his family’s past, by pressing his body to the ancient bookshelf. For Gayev, the bookshelf is an evincing object, a magical thing, like the “transparent things” Nabokov describes in his short novel about a man’s attempt to unravel the mysteries of his past. That slender volume, its title somewhat blurred, sits atop the stack of Nabokov’s books in the upper right quadrant of the photograph.

Other authors populating this photograph’s shelf, anachronistic to the probable bookshelf of Gayev’s Cherry Orchard: James Wood, Mary Gaitskill, and W.G. Sebald, for example, will not be born for roughly another half-century after play is written. Swann’s Way, the Moncreiff translation, sits beneath Gayev’s blurred wristwatch–I haven’t read it yet, having fallen in love with Lydia Davis’s essays on translating Proust and Flaubert, and wanting to make my way through her version first. In 1903, Nabokov, alive in the large stack just above Gayev’s right hand, is four years old, a stern, toddling polyglot, already collecting limpid morning light refracted through translucent bars of topaz-colored soap, holidays in Provence, and butterfly expeditions, these “transparent things” to be recalled and re-ordered in his mind much later, for his memoir, Speak, Memory.

And here are Gayev’s words before falling silent:

GAYEV: “‘Dear old bookcase! Wonderful old bookcase! I rejoice in your existence. For a hundred years now you have borne the shining ideals of goodness and justice, a hundred years have not dimmed your silent summons to useful labor. To generations of our family (almost in tears) you have offered courage, a belief in a better future, you have instructed us in ideals of goodness and social awareness….’

(Pause.)”

What a nut! A birthday party for a hundred year old piece of furniture! “Useful labor,” eh? I don’t believe Chekhov’s Gayev knows the first thing about useful labor. After the pause, Gayev’s next line is a non-sequitor about billiards. Not only is Gayev sentimental about the irretrievable past, he’s semi-incoherent. Is Gayev a reader? Does Gayev love the antique wood, or the printed words on paper on the shelves? Do the books themselves instruct a better life, or is it simply the age of the object that is so edifying to the family’s generations? Whether Gayev is an ardent lover of books or not, may not matter too much in the space of Chekhov’s pause, because of the reverence that the actor, DiStefano, or any other, brings to this posture of adoration. Perhaps this is not a “heroic posture,” as Stella Adler reminds the actor playing Gayev, but, in this silence, I see a strange and beautiful image, transparent in the Nabokovian sense.

This long hold, noted by both an ellipsis and an indented, italicized “pause,” halts the world of the play, permits the audience to observe the embrace on different terms, perhaps even to rejoice with Gayev for the existence of the bookshelf, and with the actor, for all that it holds. Perhaps, in the space of this gesture, it doesn’t matter that DiStefano is no actor. We’re all amateurs in a way, until someone else tells us that we are no longer pretending.

Inside the subtle, momentary frame of Chekhov’s deliberate pause, Gayev’s solo tableau gives the audience more than one discernible truth. Humor, sorrow, and nostalgia occupy the same image. As Nabokov writes in his Cornell lecture on Chekhov, “Chekhov’s books are sad books for humorous people….Things for him were funny and sad at the same time, but you would not see their sadness if you did not see their fun, because both were linked up.”

Apart from Gayev and his nervous tics, his excessive speeches, apart from the moving gears of the play paused around him, which will soon set themselves in motion, towards the completion of Act One and through the inevitable loss of the family estate, we watch a man in love with a bookshelf. Perhaps we see a man in love with books and imagine our own shelves, on which our favorite volumes are displayed, their heft and their smell, and their capacity for remembering those things past, as comforting as a body. What particular joys these cupboards hold for many of us.

At the Moscow premiere of The Cherry Orchard in 1904, Chekhov’s health was in decline. He was shrunken, dying of tuberculosis, and unhappy with the attention, but the premiere coincided with his name day, and Stanislavski–who played Gayev in a floppy silk bow tie and outrageous mustache–adored him, and so a celebration was held. (On the other hand, Stella Adler was certain Stanislavski’s adoration was not returned by the playwright: “Stanislavski understood Chekhov, who loved the theater but didn’t love Stanislavski very much because he bothered him.”) Speeches were made, and the playwright was showered with gifts, all of which he criticized for being too fanciful, impractical, or expensive. This is how Stanislavski describes one of the speeches dedicated to Chekhov on his name day: “‘Dear and much-respected,’ (instead of ‘cupboard’ he inserted Chekhov’s name), ‘I greet you,’ etc. Chekhov glanced sideways at me (I played Gaev) and a wicked smile crossed his lips.”

And so: Dear friend, dear writer, dear amateur, dear past, dear hope, dear venerable bookshelf of shining ideals, I rejoice in your existence.

Part 1 in this series.

And Part 2.

SOURCES

Bowers, Fredson, Editor. Vladimir Nabokov: Lectures on Russian Literature, Harcourt, Inc, New York, 1981.

Chekhov, Anton, The Plays of Anton Chekhov. Translated by Paul Schmidt. Harper Perennial, New York, 1997.

Vanya on 42nd Street. Dir. Louis Malle, André Gregory. Perf. Wallace Shawn, Phoebe Brand, Larry Pine, Julianne Moore. Channel 4 Films, 1994. DVD.

Martin, Clancy. “Uncle Vanya,” Paris Review Daily, July 2, 2012.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Transparent Things, Vintage Books, New York, 1972.

Paris, Barry, Editor. Stella Adler on Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov, Vintage Books, New York, 1999 by the Estate of Stella Adler.

Rayfield, Donald. Chekhov: A Life. Henry Holt, New York, 1997.

Stanislavski, Konstantin. My Life In Art. Routledge, New York, 2008.