One afternoon last week, on vacation in British Columbia with my family, my boyfriend and I slipped away from the boozing and card playing for a quick visit to the Vancouver Art Gallery. We arrived at the museum shortly before closing and walked into the first gallery we saw, a small dark room where we found Fiona Tan’s 21-minute, two-channel video installation Rise and Fall (2009). I loved it. I returned the next day—our last day in the city—to watch it again. (Find an excerpt here.)

A few weeks earlier, back home in Michigan, I had gone to the theater to see Terrence Malick’s most recent film, To the Wonder. The day before that, I had watched The Thin Red Line. And the day before that, Days of Heaven. I was on a Malick kick. (Still am, it seems. Last night: Badlands. Tonight: The Tree of Life.) Fast forward to Vancouver, where my boyfriend and I sat rapt before Rise and Fall. As I watched, I found myself thinking of To the Wonder and what it shares with Tan’s shorter piece. Fragments of a narrative. “A wandering, floating, probing, tilting camera.” An unabashed infatuation with natural beauty. Characters that don’t seem exactly like full characters but are somehow figures of another kind. Rise and Fall, though, succeeded for me in ways To the Wonder didn’t. Near the end of the film, my boyfriend slid closer to me on the super hip white leather bench, leaned in, and whispered, “This is what Terrence Malick wishes he was doing.”

It’s true, I thought. Terrence Malick wants what Tan’s got: beauty up the wazoo; the ghost of a narrative flickering, hovering at the edge of the screen; a real sense of intimacy; a dynamic relationship between natural imagery and character; the fragmentation of story in order to privilege mood, image and tone; and, most strikingly, montage as a primary technique.

To the Wonder is a truly beautiful film—though often, to its detriment, it is beautiful for beauty’s sake alone. The film chronicles the relationship between a sad French woman (Olga Kurylenko) and a tight-lipped American hunk (Ben Affleck). In order to be with him, she swaps Paris for a tract house in Oklahoma. Enter more sadness and disappointment. Enter a melancholy priest (Javier Bardem). Enter the hunk’s ex-girlfriend (Rachel McAdams) and the prettiest herd of buffalo I’ve ever seen. And yet for all its splendor and elegance and movement, To the Wonder “falls into a kind of gorgeous emptiness.” The characters are flattened against the sun-soaked landscape. The characters—like light through white curtains or the horizon at the golden hour—often seem like just another pretty thing in a long list of pretty things. Kurylenko especially. And here’s where I squirm. Can Malick refuse to fully characterize her and then place her again and again in shots that seem to exist for the sole purpose of gorgeousness? Can he do this without objectifying her? I’m inclined to think he can’t.

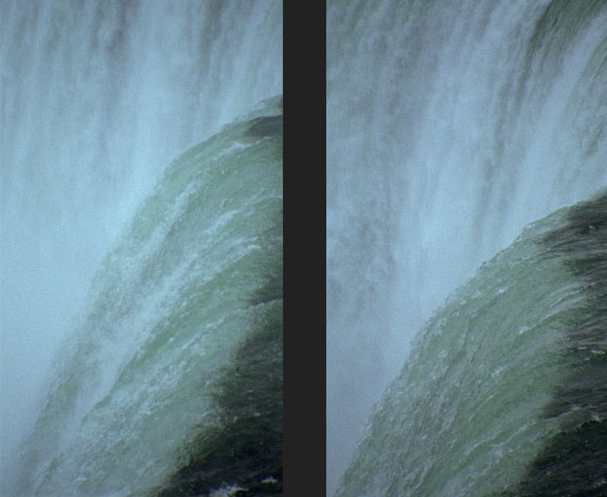

Tan, like Malick, doesn’t set out to create full or round characters. Unlike Malick, though, she insists that the women in her film are, always, real people, not objects. Rise and Fall, filmed at Niagara Falls, and in Belgium and the Netherlands, manages to be both gorgeous and full. The film, projected on two screens suspended side-by-side from the ceiling, opens with an identical shot of green rapids on each screen. Then, the first cut: on one screen, a landscape of white sheets where a woman, somewhere between 60 and 70 years old, sleeps; on the second screen, the image of water remains. This woman is one of the film’s two main characters. The other: a young woman, I’m guessing around 30, who could be—we’re never quite sure—the older woman’s younger self. We first see her as she is dressing, pulling on dark stockings, then in a peach shawl, weaving between a row of trees, playing cat and mouse with the camera. Light slants through the trees and across the grass. Cut back to the older woman: she opens her kohl-shaded lids, her face red and splotchy. Back to water on both screens: slow motion on the left, rapids in real-time on the right.

In Rise and Fall, the relationship between the two screens is ever changing and unpredictable. Sometimes images are doubled, sometimes a single image spans both screens, sometimes the screens depict different angles of the same subject, sometimes different subjects altogether. In contrast, the overall structure of the film is dependable, vacillating reliably between the two women occupied in their various daily and often intimate offices—applying makeup before a mirror, writing, walking away from the camera on a tree-lined road, running a hand along the spines of books on a shelf, allowing their own spines to be touched (or not), bathing—and images of water. We can count on Tan to rock us back and forth in this way: water, women, water, women, water. Water in so many forms: the rough quick surface of it, water crashing into more water, the mist that rises at the base of the falls. My favorite: an oddly milky stream moving through seaweed, like hands through hair. The women never speak, though the film is full of sounds. The lovely drone of the score, the soft jumble of wind and birds, water trickling, water rushing, water breaking violently.

Tan’s imagery is rich, weighted with meaning, stirring, meticulously crafted. The water imagery especially. It builds and escalates, suggesting something ineffable, baffling, and true about the movement of time, the fluidity of memory, the tension between past and future selves. Although these women’s lives are rendered only partially here, we know that, beyond what we can see, there is fullness. We’re looking at them through the murky surface of moving water, sensing their depths. We’re tracking the women’s private movements through a high window. How perfect, the double screens strung up before us in the gallery, like the very panes through which we spy their wordless intimate moments.

So much of Rise and Fall is beautiful, but none of its beauty is for beauty’s sake. Tan manages to push her visual language into the realm of the figurative—water, in her able hands, becomes a metaphor we can feel if not fully explain. I keep returning to Malick, wanting him to make a similar move, for his images to consistently and deliberately transcend their own beauty. I’ve seen all but one of Malick’s films. Fingers crossed for The Tree of Life. I’ve heard great things.