Fifteen minutes before the Musée D’Orsay in Paris closed its doors, I entered the final room of my visit to the museum and encountered two “architectes de l’étrange”: François Garas and Henry Provensal. What struck me most about the work of both artists is the technical precision with which they approached their dreamlike subjects. Of course. The young men were gifted architects who, later in their careers, would go on to receive national awards and high-ranking commissions, and both trained at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. That these pieces exist at the top of wooded mountains, reach in skyward vertical lines, and reveal interior rooms that seem to open infinitely into each other, is especially strange in contrast with images of realized architectures of turn of the century Paris. That these pieces highlight the technical skills of these architects, the mastery of line, fealty to each structure’s projected physical integrity (and if you find yourself curious, take a look, especially at the earnest series of plans, each successive drawing more convincingly applied: this building might actually work) reminds me of Gabriel García Márquez’s famous anecdote about his grandmother telling “fantastic stories with a brick face.” At the École des Beaux-Arts, Garas and Provensal, promising, young, both entering an art tinged with the useful aura of a professional trade, publicly dispensed with the authority of utilitarianism, rejected the familiar Greek lines, and discovered each other as aesthetic simpaticos.

Plans for Interior of the Artist series, Garas

Garas created a series called Interiors of the Artist, rigorously projecting the creative body as an imagined structure of rooms in these drawings. Garas’s dreamier pieces, “Temples for Future Religions,” are the most recognizably Post-Impressionist of the bunch–smudgy oil pastels in a surreal palette. Provensal’s “Dream Asylum” uses earth tones to render a meticulous utopian get-away, a glorious, exalted treehouse, containing the wonders of the unconscious mind. But his “Tomb of the Poet” is what stunned my museum-going companion and I both: a glowing ivory dome that resembles a spaceship, a holy gravesite, a marquee of seraphim. Like the cover of a dime-store science-fiction paperback, made sublime. (I wasn’t bold enough to snap a photograph of “The Tomb of the Poet” in the museum, and wasn’t able to find an image on the internet, so you might just have to see it in Paris one day, gentle reader. Provensal’s “House of Solness,” below, instead).

“The House of Solness,” Provensal, 1902

Garas created a Pantheon of Artists, living and dead, to whom his work was often dedicated: Baudelaire and Edgar Allan Poe, as well as John Ruskin, Jean Carriès and Edouard Manet among them. In the work is the sense that Garas imagined this synesthetic group of artists as collaborators as well as muses, their pantheon comprising a sort of wished-for collective. Provensal and Garas both embraced what their movement termed the Absolute. In his 1904 manifesto L’art de demain, vers l’harmonie intégrale, Provensal defined the direction of his artistic gaze, “towards those distant shores where truth is dying, and should reveal, in forms, that dream of infinity he carries within him, and which is, in the end, nothing more than the innate desire for immortality slumbering within all human conscientiousness.”

Garas and Provensal, with the other members of their unorthodox guild of architects of the fantastic, Henri Sauvage, Gabriel Guillemonat and Frantz Jourdain, revealed the tenets of their practice at an exhibit called Architects’ Impressions in 1896 at the Le Barc de Bouteville gallery in Paris. After the 1896 exhibition, a rebellious school of architecture was founded, which took on the reverence of a religion. A booklet was distributed at the reception, which declared the architects’ aesthetic rejection of “the mental slavery produced by the exclusive study of Greek and Roman architecture, and by a knowledge of nothing but the Italian Renaissance.” The designers of the Dream Asylum and the Pantheon of Artists idealized the role of the architect as one who designs beyond reality, not merely to create buildings in which humans might live and work.

If not a utilitarian one, there seems to be a cultic purpose to these two artists’ celestial architecture. In his “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin puts forth the cultic purposes of ancient art: “The elk depicted by the Stone Age man on the walls of his cave is an instrument of magic. Yes he shows it to his fellows, but it is chiefly targeted at spirits.” To my mind, Garas and Provensal’s strange school of art aligns itself with this ancient tradition of worship, with their holy houses created, as Benjamin writes, “in the service of some ritual–magical first, then religious.” The architecture of the strange speaks in several languages at once, evoking music, dreams, poetry and death. Garas’s “Temple of Thought,” an imagined building dedicated to Beethoveen, exalts the creative process to the sublime. These buildings can not exist in the world we know, nor in the one that Provensal and Garas knew in Paris during the turn of the 20th century. The future of these artists’ dreams has not yet come. But I don’t believe either had counted on their shared utopia to arrive as an occasion for unveiling the solid majesty of their exquisite templates.

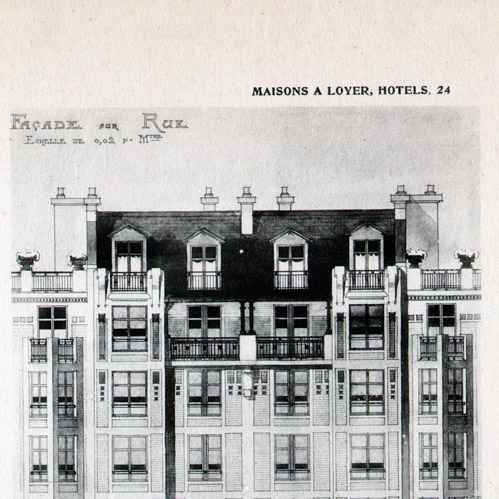

Some of Provensal’s work for Rothschild as Assistant Architect

Both men eventually turned to work. Provensal, worked in his fantastic mode for only nine years; Garas created his Temple drawings for sixteen. Professional concerns influenced Provensal to construct social housing for the Rothschild Foundation in 1905, just a year after the publication of his artistic manifesto. And in 1913, poverty moved Garas to abandon his quest for those distant shores, and he began laying bricks in his father’s employ.