1

The summer between high school and college I worked at a clothing boutique in San Francisco, taking polyester tube tops out of boxes, steaming them on hangers, and carrying them across the earthquake-dinted floorboards, which glowed golden in the midday-light, to the rounders for the shop’s wealthy patrons to admire. My boss, K-, lived in a studio above a flower shop and frequently aired her romantic woes. K- had recently had sex with the bartender at the restaurant down the street from the boutique–right behind the bar, no less!–and now she had to walk three blocks out of her way just to get home at night to avoid the bartender’s gaze through the window. He wouldn’t dare come into the store. I was 17, and K- had recently turned 25. Over the hill, she said. She chain-smoked Parliaments, pacing back and forth in front of the shop in her gleaming black heels. Men called my boss on the shop phone. We had caller ID, and she would signal for me to run to the front to answer the phone with the tepid shop greeting, depending on the number. Blacked-out one night, K- left her Louis Vuitton purse in the back of a cab. My boss was on a no-carb diet, Atkins, and scoffed at the burritos I gobbled in the break room. Empty carbs, she said. I brought a bagel in a paper bag on a morning I opened up the store, and hours later, I found a tremendous bite removed from the bagel’s side, a crevasse perilously near to the hole at the bagel’s center; such a center cannot hold. Upon closer inspection I noticed the bagel’s desperate void smelled of nicotine.

An older woman came into the shop one day, and my sense of time and balance shifted in her presence. She was sixty-ish and stunning: impossibly dainty, with a rich olive complexion and long hair dyed a crimsony-black. I attended to her in the dressing room, filling the room with new sizes and colors as she called out to me. Sweeeeeetheart! she said. The woman tried on jeans that clung low over her narrow hips, and then, appraising her body with satisfaction, she slapped her own ass. She promenaded in front of the three-way mirror in a silk halter-top gown that grazed her thighs. A suitor was taking her on a cruise; she needed a wardrobe. The other shop girls moved to the back of the store, to stand outside woman’s dressing room with me, pulled by her gravity. The woman spoke manically about the multitudes of men who wanted her, and the few she desired in return. At the time, I took her words for a dazzling display of confidence. Her body was her own; she knew just what colors, shapes, lovers, would complement it best. Trying on an olive-green t-shirt, she flashed a glittery smile, the likeness of which I would recognize on Joe Biden’s face nearly a decade later, permitted her fingers to graze her own pert breasts, and declared breathlessly, I love the way I look in green. Love it! She told me that her best friend in the whole wide world was just my age. How do you do it? What’s your secret? my boss, K-, asked, nodding at the woman’s body reflected in the trio of mirrors. A lot of great sex! the woman replied, laughing long and loud.

2

The summer I was sixteen, I worked at The Gap. My boss was a red-haired woman named M- who had recently had a baby. With the generous employee discount (60% off full-price, 30% off sale) she bought clothes–two pairs of cotton turtleneck sweaters, in lavender and lime, I remember on one occasion–and stuffed them in her shoulder bag to hide her purchases from her husband. The manager, a thin bald man with glasses, yelled at me once, when I left a receipt outside of the till. What is this? he said to me, the paper quivering in his hand. Another day, he told me about a date that went poorly. He had been set up with a younger man. Too young. Swearing all the time. Really immature. Drinking too much. At first, the manager’s words confused me, as I classified swearing and drinking with the territory of mature adults roaming freely in the world. The more I thought about it though, the more sense it made.

A girl close to my own age had recently come to San Francisco from Moscow with her family. One late night during inventory, she invited me to go to a rave with her and her boyfriend. She compared the process of attending a rave–she’d been to several Bay Area raves, though she had lived in the States less than a year–to that of a treasure-hunt. Clues were scattered all over the city, leading to an appointed field in the suburbs. You needed a car. You had to know where to look. False signs and symbols were planted to throw novices and personas non grata off-course. Elusion of the cops. We can sleep in my boyfriend’s car, she said. The year was 1999. Despite my innate teenage-girl hubris, the word “rave” frightened me. I feared an overwhelming prevalence of a drug called ecstasy (X-tasy?), and I’d heard of kids drinking outrageous amounts of water to compensate for ecstatic (X-tatic?) thirst, of dying in this way. I was too self-conscious to believe I might command a glow-stick in a convincing manner, and I had no understanding of the music called “trance.” I did not possess the persuasive verve to validate this outing to my sensible parents. But I was too shy to say no without a proper excuse. I told her I had plans with my crush, a boy I told my Muscovite friend about when we folded t-shirts at night. I had no such plans. Later on, the friendly Muscovite told me that she had sex with her boyfriend for the first time that weekend, in the shower (they never made it to the rave). I was impressed.

3

The summer after eighth grade I answered phones in the rectory of a Catholic Church. My desk faced the front door, which was a frosted glass panel etched with the image of a crucifix. A tiny television sat inside a cabinet beneath the desk, and I was permitted to use it as I pleased. I had the high-minded intention of completing my summer reading and of writing a collection of short stories at the rectory desk, however, and the presence of the television shamed me. I used it as a reward. Ten phone calls fielded, one half hour of the television. A page of my own work, the same reward. The pastor tended to emerge into the rectory lobby from his upstairs quarters in cat-footed silence. Nervous shame overwhelmed me when I was seen watching the television. I feared I would be considered frivolous instead of serious and book-loving. When the pastor appeared in the doorway, I shut off the television set and pushed the cabinet door closed over its graying face. I pretended to have been reading Nectar in a Sieve all along. The pastor’s face reminded me of the consistency of raw ground beef, and his stomach jutted like that of a woman nine months pregnant. Rumor had it he drove a forest-green Jaguar he kept parked in a secret lot, and he had convinced the Archdiocese to install a hot tub in his bathroom. He’d held tapered candles crossed at my neck each year on the Feast of St. Blaise and sent a cloud of incense from his consecrated censor into my nostrils at my friend’s Tata’s funeral. When I was in the second grade I had been afraid to confess my sins to the pastor, afraid of his stern raw beef face. I preferred talking to the priest I found warmer, through a confessional screen; the other priest was always drunk, but I didn’t know it at the time. Years later, when I worked at the rectory, I wasn’t confessing my sins to any priest at all. Towards the end of the summer I would make phone calls–to my best friend, who would attend an all-girls high school in the fall, to a boy we both thought was cute. Sometimes I would see the light next the pastor’s line flash green on the rectory phone’s display panel, and hear his breath in the receiver, and I would hang up.

The rectory employed a cook named N-. N- bicycled to work and made potato gratin and quiche Lorraine for the priests, things I had never eaten at home, that fascinated me because they came out of boxes. I would push open the heavy wooden door to talk to N- in the kitchen. He always wanted to talk. About the woman he had waved to in her car on his ride over to the rectory. About a date he had gone on that ended poorly. I would cross and uncross my arms, because sometimes uncrossed arms made me feel vulnerable, but crossed arms I had heard signified rudeness. I would get nervous and slyly check the watch my parents had given me for eighth grade graduation, afraid I had been away from the front desk for too long. N- never seemed concerned that I had left my post. N- would feed me cookies that originated in a tin cylinder and just keep talking. He was an adult, had worked at the rectory for longer than me, so I stayed in the kitchen and listened. A date went well, but there wouldn’t be another. Why not? I asked, nodding to show compassion, understanding. Well, we had dinner, saw the movie, did everything. Nothing against my religion though. Everything but. Where else is there to go? he said. Nothing against my religion, he repeated slowly. Everything but. At the time, I didn’t understand what he meant, or whether it was an appropriate conversation for a forty year old man to have with a thirteen year old girl. I nodded again, and something told me to tell N- that I heard the phone ringing on the other side of the wooden door, and I ran to get it.

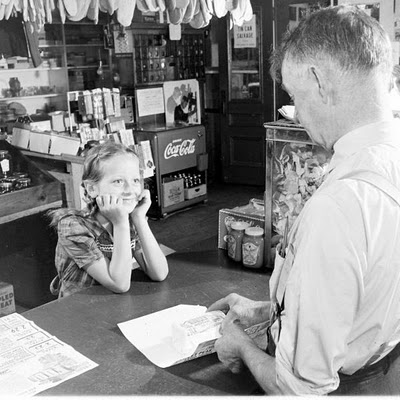

The image was taken by Eric Schaal for Life Magazine in 1942.