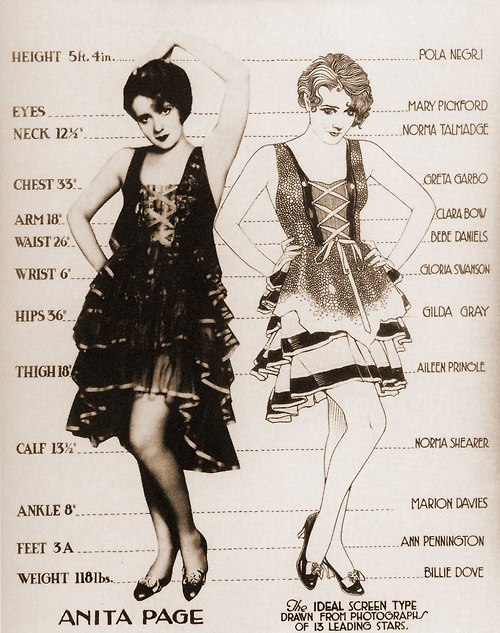

In 1928, a group of Hollywood film studio artists drew “the ideal screen type.” An amalgamation of the famous disembodied parts of Hollywood stars, the ideal screen type was doe-eyed and fair, holding her willowy arms at a coy akimbo. Beside the artists’ illustration of the composite ideal appeared the remarkable photographic image of the composite ideal’s real-life double: silent film star Anita Page. Born Anita Pomares, in Flushing, Queens, Salvadoran-American silent film star Anita Page possessed a beauty that was uncannily familiar: the eyes of Mary Pickford, the smooth white arms of Clara Bow, and the wasp-waist of Bebe Daniels. Had the camera trained its lens more closely upon Anita’s exquisite nose, this shot would have recorded her beautifully-full Latina nose as well. But beyond her composite physicality, Anita was also described as simultaneously both “a blonde, blue-eyed Latin” and “The Most Beautiful Girl in Hollywood.” No other Latina actress in Hollywood of the 1920s and 30s, aside from Anita Page, achieved star status without either effacing or caricaturing the Latin aspects of her body.

Anita’s Latina counterparts had two options: to anglicize their names and bodies in order to obtain star roles and mainstream appeal, like Rita Hayworth, or to play up a stereotyped version of Latina-ness by speaking broken, accented English, and flying into fits of uncontrollable temper and dancing, like Lupe Vélez, for example, who was known as “the Mexican Spitfire.” But Anita Page was different. Unlike other Latina actresses at the time, Anita Page could have it both ways. She changed her name from Pomares to Page, but her blue eyes were her own. She was not, however, encouraged to pass as white: reporters never failed to remark on the fact that she was both a bona fide star and a Latina. Anita Page played drunken floozies falling down stairs and tomboys playing baseball as often as she played glamour girls–but rarely was she forced to play the Spitfire. Page’s ethnicity–despite her natural fairness and the industry-motivated anglicization of her name–still remained a part of the conversation about the star. Anita could pass for white, but didn’t–at a time Hollywood actually did want Latinas on the screen.

In 1939, FDR’s Good Neighbor Policy instituted US non-intervention in Latin American affairs, and this policy extended to the film industry as well. Filmmakers during this era sought to promote unity between North, Central and South America against the Axis powers, and with the European market closed to US films, Latin American movie consumers became even more important to the US film industry.

Latina actresses became especially desirable to studios like MGM, where Anita Page was signed. Conveniently, Anita could perform both roles required of her: the blonde bombshell and the symbol of political goodwill. Because of her fair skin tone and “composite body” the Salvadoran-American Anita Page appealed to mainstream movie-watchers as well as to the interest of the Good Neighbor policy, which mandated that Hollywood provide visible roles to Latina/o actors, to supplement the central tenet of the policy: the US government’s stance of noninvolvement in Latin America.

At the height of her fame, Anita Page received more fan mail than anyone in Hollywood, more, even, than her rival Greta Garbo. One of Anita’s most ardent admirers was Benito Mussolini, who sent Anita hundreds of letters, many of which included marriage proposals. However, MGM forbid Anita from replying to Mussolini, and insisted that Anita tell no one of the Italian dictator’s love for her. But Anita’s mother Helen, who Anita had hired as her personal secretary, believed that each fan deserved a handwritten response, and so the brown-skinned Helen continued to write to the Fascist dictator, signing her fair-skinned daughter’s name, marking the page with a lipstick kiss, even as Mussolini began to align himself with Hitler. So much for the Good Neighbor policy.

Anita Page performed her ethnic ambiguity during a time not too different than today: when Latinas were in demand in the arts for political reasons, and simultaneously subjugated to stereotype. I write that Anita Page performed her ethnic ambiguity not to flatten out her identity, but to imagine the complexity therein that was denied by Hollywood’s lens. Ambiguous ethnicity can be confusing, mostly to the person of color who possesses an ethnicity perceived by others as ambiguous. When I was awarded a high school scholarship from the Italian Catholic Federation, my parents scrutinized the fine print of the award notification, saw nothing banning an eighth-grader of Salvadoran and Yugoslav parentage from accepting the prize, shrugged their shoulders, and said, “Alright.” But sometimes the perception of ambiguity raises the question of what a person of a certain background is “supposed to look like,” as if the observer is entitled to visible clues to better categorize the human histories of others by sight. “I’ve been looking, but I can’t figure it out. Will you help me settle a bet with my wife? Where do your parents came from?” a stranger said to a friend of mine in a restaurant, after approaching her with a pointed finger.

Within her own family, Anita Page stood out as the güera, in terms of status and color. Anita hired her father, John, as her chauffeur, her brother, Mario, as her personal trainer, and, of course, her mother, Helen, as her personal secretary and forger of love letters. Like Anita, I have a brother named Mario, and a brown-skinned father who worked for many years as a chauffeur. I know my father, but I can not claim to know Anita Page’s. How could I know a man based on the information given? What does a brown-skinned chauffeur look like? How does he behave? I assure you that my brown-skinned chauffeur father is not an amalgamation of the man you have seen on television one hundred separate times. He’s a classical guitarist who played semi-pro soccer as a young man and quotes Cervantes by heart. He wears white button-down shirts and Basque berets. His first language is Spanish, but his English is perfect, more strictly measured than that of any teacher of my youth. My father’s bigote is out of this world, mightier than anything in theaters.

In the last week, a young white female writer has been receiving some well-deserved flack for her all-white casting choices in the pilot episode of her new HBO show. I’ll limit my commentary on the show to the conversation surrounding this director’s problematic attempts to cast non-white actors. Racialicious published a screenshot of casting notices for the show. “Actresses of color needed include a Jamaican nanny (“overweight, good sense of humor, MUST DO A JAMAICAN ACCENT”) and a nanny from El Salvador (“sexy, MUST DO A SOUTH AMERICAN/CENTRAL AMERICAN ACCENT”).”

How atrocious, how boring, and how disappointing. Also: barf. This uninspired, essentialist approach to providing diversity onscreen is nothing new. Long before the creator of the controversial HBO show was born, Lupe Vélez was stuck as the Mexican Spitfire, scandalizing upper-crust white folks as she swung outside of drawing rooms on window-washing equipment, engaged in food fights, and demanded immediate sexual satisfaction in angry, broken English. Ah, the rich and varied history of perfunctory inclusion. I imagine the rooms where those “artistic decisions” are made these days are acoustically-rich with the sonorous phrase, “I’m not racist, but–.” On loop.

Another Lupe, contemporary Latina actress Lupe Ontiveros has played over 300 maids during her acting career. However, Ontiveros desires complex roles that break the stereotype of what a Latina can be onscreen. In an interview with NPR, Ontiveros says, “I long to play a judge. I long to play a lesbian woman. I long to play a councilman, someone with some chutzpah,” but unfortunately for Ontiveros and for her audience, maid roles are what continue to be offered to her. For every righteous decrier of such stereotypes, someone can be found, lurking in the comments section or speaking loudly at a bar, who thinks that Latinas should just be content to be working in Hollywood at all. As Dodai Stewart writes, in her response to Devious Maids, a new television show that happens to star four Latina actress, “Some may argue, “at least she’s getting work.” It’s true that being a working actor is rare and commendable. But being pigeonholed, playing a character that has been written from a white person’s perspective of what a Latina thinks and feels doesn’t do much for how our society views women of color. Not all Latina women have accents. Not all are under-educated. Not all work as domestics. They are doctors, lawyers, politicians, artists, writers.”

So what is it? Are dark-skinned Latina actors relegated to domestic work onscreen because they are considered unpalatable to consumers of mass-media, unable to portray likable, complex protagonists? Must light-skinned Latinas play white to be successful? I’m reminded of an essay on the perils of navigating an ethnic identity that is complicated by perceived ambiguity, by Heidi Durrow, author of The Girl Who Fell From the Sky: “In New York City, after graduation, I realized that I looked Dominican to Dominicans, Bangladeshi to Bangladeshis, Puerto Rican to Puerto Ricans and Greek to Greeks. There was a vast difference between what people saw me as and the complicated identity that I hid behind my accommodating smile. Because who, after all, has ever heard of an Afro-Viking?”

Complicated identities hide behind accommodating smiles. If someone hasn’t “heard of someone like you,” you must not exist. In cases of complicated identity, it can be easier to let people see what they want to see. In the cases of lighter-skinned people of color: to permit ethnic identity to become invisible by effacing the complicated nature of who we are, what worlds we represent, in an effort to be recognized as relatable to a larger audience, as universal. In the cases of darker-skinned people of color: to give the audience what it has been conditioned, by contented, staid casting/publishing/funding choices, to desire: the pleasantly plump Latina maid, the sexy spitfire, other knee-jerk iterations of the other. The industry promotes an environment in which it is easier to duck one’s head and play identity for predictable laughs than for an artist of color to be complicated, interesting. This model assumes an audience of simpletons. Apparently, striving for the Platonic form of “stock other” (be that other a goofy, magical or sexy form) sometimes yields employment. Lupe Ontiveros is no more “wrong” to take the roles offered her than Anita Page was, but it’s certainly exciting to observe her extraordinarily brave, public-forum questioning of why Latinas are not offered a wider variety of roles.

Why are popular representations of Latinas denied complex humanity? As Kendra James writes, “[W]hy are the only lives that can be mined for “universal experiences” the lives of white women?” I’ve written before about how I often wonder why a published work of literary fiction written by a Latina must bear a chile-spiced mango on its cover. Writer A.L. Major puts her concerns about being a writer of color writing about characters of color this way: “there’s a great possibility that the people I care about, the characters I create, are worth less in my readers’ eyes, that my characters’ horrific deaths and tragedies are just not as sad as their white counterparts. Or, worse that unless I make their ‘blackness’ something as tangible, as recognizable, as what we believe blackness should look like, my readers might rewrite my characters all together. And not in the good way, not in the way you strive for as a writer, where people recognize the common threads that connect all of us as humans, but the more horrific sense of identification, where humanizing means whitening, where full empathy with a character cannot be achieved unless that character physically looks like the reader.”

Authentic representation can not be claimed from these margins; we must not pretend to be invisible. Because, surely, someone out there must want to see people of all colors represented in film, on TV, in literature, with gobs of chutzpah and welcome complication, right?