Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven & Hell

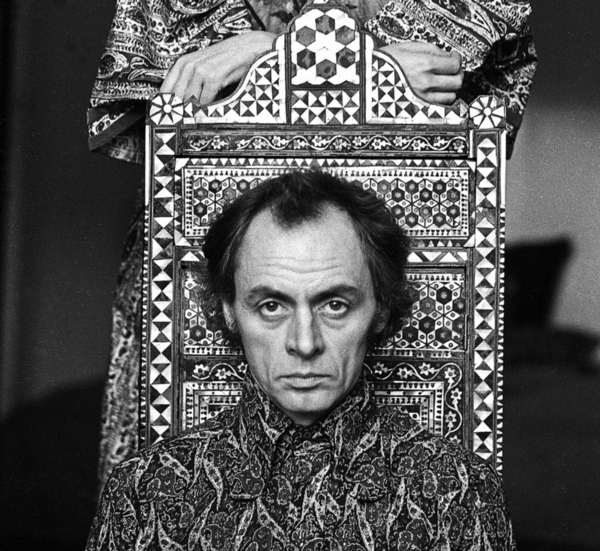

Last weekend I went to the Institute for Contemporary Art in London for a screening of the first feature length film by the Scottish film and video artist Luke Fowler. The film, All Divided Selves, is a kind of documentary portrait about another Scotsman, the late psychiatrist R.D. Laing. I say “kind of” because there isn’t any sort of narrative; having never read any of Laing’s work I didn’t come away knowing much more about his contributions to the science of psychiatry or his ideas. Instead I found myself lulled into a dozy dream state occasioned by a dazzling assortment of sound and image.

Fowler’s film is an art piece and makes heavy use of the vocabulary of experimental video art that has little to do with conventional use of sound and image in the cinema. Fowler cuts and chops archival footage – interviews with Laing, his patients and scenes of 1970s London and Glasgow – with his own work – landscapes filmed in extreme closeup, colorful abstractions reminiscent of early abstract video art like Stan Brakhage, a fly struggling in a pool of honey, a melancholy and hauntingly beautiful folk tune.

All Divided Selves straddles the worlds of the cinema and the gallery, merges them – a feature length objet d’art – and where it fails as a narrative (though I don’t think this was really Fowler’s intention) it succeeds at depicting a very particular sense of ‘place’ through audio-visual description; something less linear than you would read in a Wikipedia entry on Laing’s life, something ambient, erratic, impressionistic, unspecific, but above all it gets at something of the essence of the cultural and social conditions in which his ideas arose and were influential. Laing was something of a countercultural hero and the footage of artists and bohemians who took a fancy to his ideas about madness and normality is perfectly nostalgic.

I came away thinking not about Laing’s ideas but about ideas in general. What happens to ideas over time? How do they live, change and disappear? Can they survive in another context?

Artists have been thinking about the past for a long time. But typically within the context of their art-historical precedents. The history of art can often be seen as a conversation between adherents of different styles, the creation of new visual vocabularies in response to something that came before it. A lot of artists are closet academics, citing their sources – albeit often rather cryptically – while attempting to update something by placing it in a new context.

But what happens when artists don’t restrict themselves to art history? A lot of artists these days work with archives. It’s probably worth noting that Warhol did this in the sixties with screen prints of photographs documenting car crashes and death row prisoners. It’s important to push the boundaries of the relationship between culture and other fields. Artistic work with archives is a strategy for achieving this. Nothing is relevant if it can only exist in a cultural or intellectual vacuum.

Artists who begin with archival material re-present the content of the archives in order to ask questions about the past’s relationship to the future. The past becomes the main vehicle for thinking about new possible worlds. Fowler’s film abandons narrative in favour of affect. The complexity of the relationship between image and sound in his film echoes the complexity of the relationship between the past and the present, fact and opinion, progress and nostalgia, ideas and the cultural and socioeconomic conditions in which they arise. What Fowler’s film means isn’t really important. This hybrid art piece is pointing ahead while looking back, telling us the only way forward is to appropriate and redefine.