Lev Grossman begins his recent Time article, writing “For every minute that passes in real time, 60 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube…Sixty hours every minute. That’s five months of video every hour. That’s 10 years of video every day.” How is that possible? Most often YouTube’s content includes movie clips, short films, whole films, television shows, music videos and amateur videos. “Anybody can run [a YouTube channel] easily and for free. That puts individual YouTube users on the same footing with celebrities and major networks.” I don’t know if I’d call them celebrities, but recently, I’ve developed this immense fascination with the people who have video blogs (vlogs). I think of vloggers as kindred spirits, all of us propelled by our shared need, not to gain celebrity, but to tell their stories and to enter into conversations that were once dominated by corporations and TV networks.

Not all vloggers sit wistfully in front of their laptops, as I do, agonizing over the perfect sentence; some videos can be incredibly boring to watch; some are not so much stories as they are random details strung together; but there are few that speak to the fundamental need that all writers possess. In particular, there’s this group of black queer women, who call themselves studs (or studz). In their videos some dance, some answer questions, like do straight girls like studs, some tell their stories of how they came out. Most videos might be too scandalous to post here. Studs, and others like them, have learned why it’s important to tell your own stories; better to get them out. I know what happens when you suppress your stories or worse when you never seek them out.

My mother and I do not speak to each other. Sure, we talk of polite niceties; we play a fierce game of Scrabble every week, but what I know of her and her life before I became a witness to it wouldn’t stretch further than my index finger. Born in the Bahamas, as was I, my mother has only ever told me small sections of her story. As a child I would ask her: Who were her parents? Were my ancestors slaves? She would always answer, “I don’t know.” At first I assumed she was lying, shrugging off my questions because I was a child. It might be because I’ve longed so dearly to hear the stories of the women before me I’ve felt compelled to tell my own, or at least, fragments of my stories in the fiction I write. Gradually, I’ve come to realize my mother truly may not know who her father was, or who her grandfather was, and that I may come from a line of woman who never truly heard their stories, or learned why they should tell them.

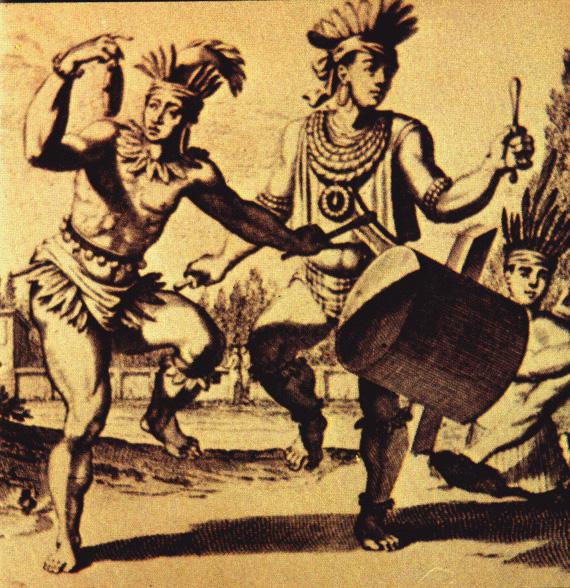

Without a sense of history, my Bahamian heritage sometimes feels barely recognizable. When I read recently about a fire that started in an important cultural museum that destroyed most of the artifacts documenting Bahamian slavery, I felt as though I was mourning what never truly belonged to me. Further back still: before Christopher Columbus “discovered” The Bahamas, there lived a benign tribe called the Lucayans, whose culture and history is mostly lost to Bahamian scholars and citizens because their stories were never documented. This tribe of people that once existed, now simply do not and there is little to show they ever did. How is that even possible?

It might be too late for my mother to develop the skill to tell stories, but I’m excited about the generation that’s learning to tell their stories, even if those stories are questionably rendered and uploaded on to YouTube.