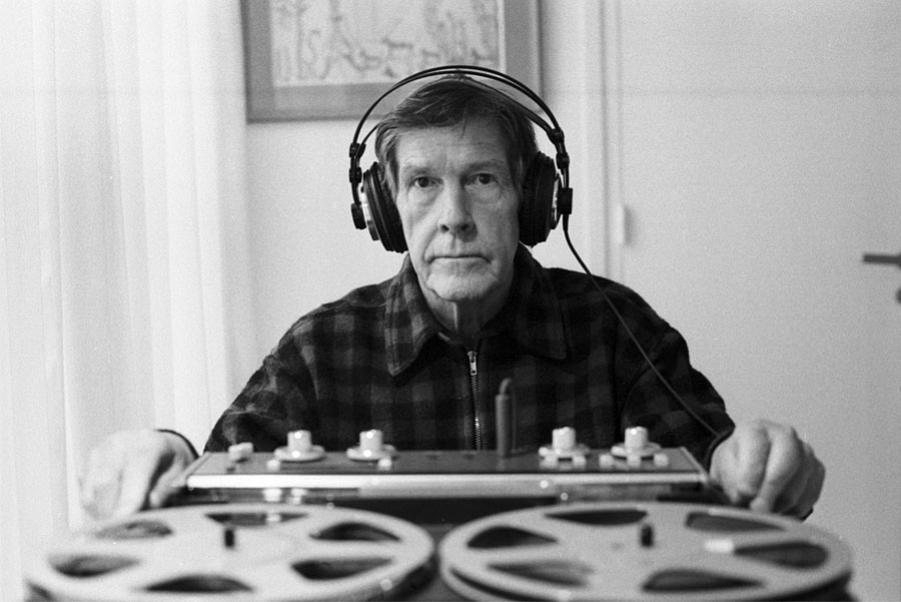

“The first thing I ask myself when something doesn’t seem to be beautiful is why do I think it’s not beautiful. And very shortly you discover there is no reason.” — John Cage

When John Cage began experimenting with chance operations in the 40s, he was looking for a means of stripping intention and taste from the process of creating art. In the Western world the notion of “genius,” at least as it relates to artists and performers, is generally shaped by a psycho-historical method of decoding biography to discover the seed of ability. In the pre-modern world, it was taken for granted than an artist in full possession of his faculties, having taken care to hone his craft, could be compelled by divine will or religious mania to make a work of lasting value. After Freud and Nietzsche, we began to see our manias and urges as beginning and ending in the self. If the artist used to be a kind of Jacob, forever wrestling the angel into submission, now he is at best a lesser Hercules laboring to exorcise the demons of his parentage, or at worst a nebbish, fretting with his head in his hands and one foot in the analyst’s door.

Intention, mighty though it sounds, is always yoked to personality. One of the reasons that artists are so hesitant to discuss their ‘intentions’ is that any talk of intention pretty quickly boils down to I-like-this-I-don’t-like-that. Or, conversely, an artist talks at length about his intentions, parsing every feature of a finished work in terms of its relation to his ‘designs.’ This kind of talk, even when it is enlightening, is embarrassing. It debases the artist by highlighting his failures, it debases the work by stripping away every trace of mystery, and it debases the audience by forcing them into the role of shrinks or sleuths.

Then along comes Cage. Early in his apprenticeship Cage was warned off composing by his tutor and mentor Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg believed that Cage had no ear for harmony and that Cage, if he continued in his studies, would sooner or later arrive at an insurmountable wall. Cage’s response was and is a call to arms for every would-be artist since Pound and Picasso: “Then I will devote my life to beating my head against that wall.” If nothing’s new, then nothing’s old; whap your head against the wall and see what comes of it.

Inspired by Duchamp and the teachings of Zen Buddhism, Cage relied on the I Ching and other chance operations to compose—and I think compose is the right word—music that transcended his intentions. By moving his music outside of the sphere of his own likes and dislikes he created pieces that resembled acts of nature; the joy of creation, of manifesting one’s own will, was replaced by the simpler, sweeter joys of observation and surprise. Cage expected he would find the results interesting and he usually did. He did not create in order to reproduce what he liked, he created in order to find out what he liked. This was part of his project as an artist, to investigate his taste and temperament, and to cultivate an enormous openness. He wanted to put himself in the position of the child, for whom the newness of each experience makes it a potential site of joy.

“I have nothing to say,” Cage has said, “and I am saying it and that is poetry.” Is there any single statement that both typifies and defies the post-modernist problem with more heart and aplomb? Whatever his virtues as an artist and creator, there is no denying Cage’s bigness of will. He made his discipline a virtue in and of itself. Critics of Cage like to point out that his reliance on chance operations was so rigorous that it left ‘nothing to chance,’ a clever bit of mockery, but I still find Cage and his project to be breathtakingly courageous. This is the greater Hercules, the artist who labors absolutely to remove every last trace of intention from his art and leaves us puzzled but amused. The pieces that resulted were obsessive rather than systematic, hot rather than cold, and, paradoxically, as personal as a work of art can be.