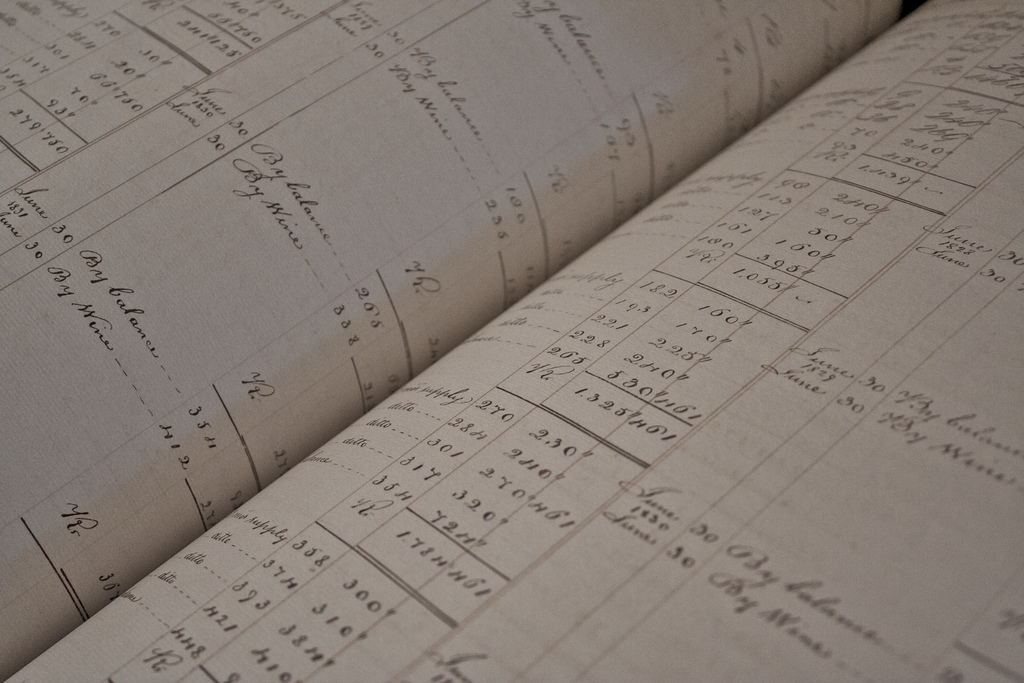

Among some of my oldest relatives, there’s a custom of recording weddings gifts given and received in order to ensure that no family is left feeling cheated. So, for example, if Jupiter Uncle gave Volkswagen Uncle’s daughter one thousand and one ringgit* on the occasion of her marriage, then when Jupiter Uncle’s son is getting married, Volkswagen Uncle will consult his wedding-gift book, look under Jupiter Uncle’s name, and duly stuff one thousand and one ringgit into the clean white envelope he will slip into his shirt pocket on the morning of the wedding. The custom works in reverse, too: Jupiter Uncle will write down in his own book what he gave at Volkswagen Uncle’s daughter’s wedding, so that he will know exactly how much to expect when his own children are getting married.

The system takes into account different family sizes: should Jupiter Uncle have three children, but Volkswagen Uncle only one child, then Volkswagen Uncle is expected to return the one thousand ringgit in three installments. Allowances are also made for different financial circumstances, so that an immensely wealthy uncle might give generously to his nieces and nephews without expecting equal gifts for his own children if his siblings are not quite so wealthy. These allowances notwithstanding, I used to hate this system, for all the reasons that have probably already struck my Western readers. It seemed to mandate what should have been natural and voluntary, to value appearances over sincerity, to throw families into agonies of shame. In my eyes the system remained unredeemed even by the comedy that arose out of it: the men, like my ne’er-do-well uncle, who made a profitable hobby of gatecrashing weddings with the requisite envelope in their pockets (with their eye on that envelope, neither the bride’s side nor the groom’s would throw out such a guest even though neither side recognised him); the families who, when going through the envelopes after the wedding, had to cast aside those empty unmarked ones, like spoiled votes.

But I’ve been thinking about that custom this week, about what we expect in return when we give, about whether it’s possible to ever give anything without remembering, somewhere at the back of your mind, that you gave, how much you gave, how readily. You may not record it consciously at the time, you may have no intention of keeping tally, but one day when you’re least expecting it, the memory of what you gave will surprise you.

On June 14th, the BBC’s Channel 4 released Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields, a documentary about the final weeks of the 25-year-war between the Government of Sri Lanka and the Tamil Tiger rebels. At least 40,000 Tamil civilians died in those final weeks, herded into “No-Fire Zones” and then targeted by government forces and used as human shields by the Tamil Tigers. Trailers for the documentary warned that it contained “the most shocking images ever seen on Channel 4,” and certainly, having seen my share of televised atrocities — we are spoiled for choice, after all, and I tend to force myself to read and watch the worst of what there is — I will say that these were the most painful fifty minutes I have ever spent watching anything on a screen. There are those who have argued that SLKF sacrifies insight for shock value, that its bloodshed-as-exhibition thrust is in terrible taste. I don’t necessarily disagree, although we all know how hard it already is to get any attention for whatever the world’s latest tragedy might be; shocking images draw an audience, and that has to be the producers’ top priority whether their primary motive is political or financial. But I’m not here today to discuss the merits of the documentary. I’m here to talk about the only field in which I’m an expert: my own feelings.

Although I have no ancestral ties to Sri Lanka, I am of Tamil descent. Tamil is the language in which my grandmother spoke to me, the language of her love, of her protection; it is a language inseparable, for me, from both the bliss and the melancholy of my childhood. It’s also the language of fierce emotion: the ugliest insults, the most uninhibited joy. Although I write only in English, when I’m really angry or really sad, when I’m feeling lost or confused, my tongue rebels against not only the vocabulary of English but its very sounds, reverting to Tamil phonemes. It’s an almost physical transformation — I can almost feel my tongue changing shape inside my mouth — and anyone who is with me at these moments notices the abrupt switch in accent even if I’m speaking English.

So it’s no surprise that it is especially difficult for me to hear people pleading for the lives of their children, screaming for their mothers, or begging for mercy in Tamil. But I suspect that even this does not begin to explain to a Western audience the power that spoken Tamil holds over me. I asked my husband, who is American and white, if his heart lurches every time he hears someone speak American English on the radio or on TV. I expected him to say no, and I recognise that this may be just my husband, who is known for his equanimity rather than for his lurchy heart. Still, I do think that my relationship with the Tamil language owes itself not just to my childhood, but to two other facts of my life: 1) that I have never, at any point in my life, lived in a place where I was a member of the ethnic majority; 2) that I left home relatively young, and have never gone back to live there. I won’t call it exile — I have trouble with applying that word to myself — but I do think that your connection to a place, a language, a culture changes when you have to leave it forever. There’s an ache, an absence, that doesn’t go away.

I’m telling you all this to explain the reaction I had to SLKF. By any standards it was an extreme reaction; I wept not only while watching it but for days afterwards, in the shower, while trying to sleep, with no warning while I had — or so I thought — other things on my mind. And weeping, I found myself going back to the long black book I apparently keep inside my head, the one marked Sympathy Given and Received. I thought of the attention I have paid, the outrage I have summoned up, the pain I have felt for what I did, yes, in this lowest of moments, think of as Other People’s Causes: Rwanda, Bosnia, Gaza, The Congo, Zimbabwe, gay marriage, the election of George W. Bush not once but twice, universal healthcare in the US, the Tea Party movement. I thought — of course — of September 11th. I thought of the tears I’d shed and the people I’d shed them with, the hugs I had dispensed, the fury I had witnessed and vicariously felt, the cries for revenge that I listened to and forgave. I thought of how, in the days after September 11th, I would never have asked an American, breezily, nonchalantly, on the phone or in person, How are you? let alone expected an answer about his or her everyday life, the deadlines at work or school, the social engagements. I would never have asked because in those days and weeks, everybody knew how Americans were, and nobody assumed — as many of us seem to assume every day — that politics are separate from real people’s lives, that the events playing out on the global stage are not the things that affect our day-to-day feelings, our appetites, our desire to get out of bed in the morning. It’s socially acceptable to be sad or angry about things happening directly to you or to people you know; it’s not socially acceptable, in most circles, to cry all night about a documentary involving people you have never met in a country you have only visited once. I thought of why it was so difficult for me to answer even a close friend or family member’s How are you? with the truth: My heart is breaking because I watched a BBC documentary about Sri Lanka. I thought of my own deep need for politeness and calm, of why I respect social conventions and avoid confrontation even when doing so hurts me.

And adding up the total of my gifts of sympathy and empathy — subtracting here, carrying one hug over to another column there — I thought, also, of how much I myself am to blame. I did everything I could to fit in in America, at least in the early years, because that is who I am: a chameleon, a fitter-in. I will do your accent to make you feel more comfortable. I will speak your English, whatever its idiosyncracies, after listening to you for ten minutes. Of all people, I have the least right to be offended when Americans forget that I am not one of them.

Add to this the fact that I am Malaysian by nationality, not Sri Lankan, not even Indian, and that most people in the US and Europe don’t know the complicated relationship between ethnicity and nationality in Malaysia (I may be fourth-generation Malaysian, but I am not Malaysian Indian in the same way that a fourth-generation American is German-American or Irish-American). And then add to that the fact that I myself, having grown up under an apartheid government, argue in public for equal rights for all Malaysians regardless of descent, and that in arguing for those rights I emphasise the precedence of nationality and national identity over ethnicity and ethnic identity. If I argue that Malaysian Indians should be accepted as Malaysians, that we have no homeland other than Malaysia, that it is the Malaysian government who should address the problems of the Malaysian Indian community and not any Indian government or political party, then maybe it’s unfair of me to expect the rest of the world to understand that what is happening to Tamils in Sri Lanka is happening to my people.

The day I watched SLKF, I was sitting in bed at my laptop, my Facebook news feed on the screen. My daughter, who is two, came up behind me, and she did that thing she always does, pointing to each thumbnail, saying Baby! Dog! Tree! It so happened that on that day the profile pictures of several South Asian women were in my news feed, so as usual, my daughter pointed to each of them in turn, exclaiming — with joy, with affection — Amma! Amma! Amma! It’s a running joke in our household that to her eyes, every Indian woman is her mother. But then she came to a still from SLKF, in which a woman, mostly naked, lies dead in a pool of her own blood. She pointed at the picture, and with slightly less joy in her voice, said, Amma.

Of course I am not that woman. I cannot claim to know what any of the dead, maimed, or orphaned in Sri Lanka have gone through. I had a comfortable, middle-class childhood of piano lessons and ballet lessons. But I do know, first-hand, the devastating effects that nationalist projects can have on minorities. And I do also know that sometimes all I want is simple recognition, no analysis, no explanations solicited or given. In that moment, my daughter’s hot, sticky hands on my knee, in front of me this woman whose life could not have been more different from mine, what I felt most of all was gratitude to my daughter, for giving me something without knowing she’d given it, for expecting nothing in return.

~

*it is considered bad luck to give a round figure; you always give eleven, fifty one, one hundred and one, etc.

[Photo credits: Accounts book by futureshape on flickr; Sri Lanka 1993 by Ulf Bodin on flickr; India-faces-generations by mckaysavage on flickr]