Meet Iain Haley Pollock: Philadelphia-based poet, English teacher at Chestnut Hill Academy, and co-host with his partner Naomi of an occasional culinary smackdown based on “Iron Chef.” Iain’s first book of poems, Spit Back a Boy, won the 2010 Cave Canem Poetry Prize and will be published in June 2011 by the University of Georgia Press. I conducted the following interview with Iain via e-mail, but you might imagine the ambient noise of Hobbes Coffeshop in Swarthmore, PA, where Iain and I have met from time to time to talk about poems: a whirring espresso machine and clattering mugs. Fork tines clinking into bowls of an elusive truffled macaroni that suddenly disappeared from the local menu. The tap-tap of Iain adding more ketchup* to his macaroni. And amid the clamor of the everyday, the sound of Iain reading aloud a remarkable poem called “Chorus of X, the Rescuers’ Mark,” a poem that I am thrilled to share here in an audio clip as part of this interview, along with Iain’s comments on the major preoccupations of his manuscript, poetic inspiration and form, and the recent controversy over Tony Hoagland’s poem, “The Change.”

Meet Iain Haley Pollock: Philadelphia-based poet, English teacher at Chestnut Hill Academy, and co-host with his partner Naomi of an occasional culinary smackdown based on “Iron Chef.” Iain’s first book of poems, Spit Back a Boy, won the 2010 Cave Canem Poetry Prize and will be published in June 2011 by the University of Georgia Press. I conducted the following interview with Iain via e-mail, but you might imagine the ambient noise of Hobbes Coffeshop in Swarthmore, PA, where Iain and I have met from time to time to talk about poems: a whirring espresso machine and clattering mugs. Fork tines clinking into bowls of an elusive truffled macaroni that suddenly disappeared from the local menu. The tap-tap of Iain adding more ketchup* to his macaroni. And amid the clamor of the everyday, the sound of Iain reading aloud a remarkable poem called “Chorus of X, the Rescuers’ Mark,” a poem that I am thrilled to share here in an audio clip as part of this interview, along with Iain’s comments on the major preoccupations of his manuscript, poetic inspiration and form, and the recent controversy over Tony Hoagland’s poem, “The Change.”

Tell us a bit about the book’s evolution. When did you begin these poems? Did you envision them as part of a manuscript when you began, or did some themes and threads emerge as your work unfolded?

Well, I’m a grandiose sum’bitch, so I think of poems (and evolution) in terms of space and time. While the places I’d lived before–Southern California, D.C., Utica, Boston–factored into the content of poems, they were all written in Syracuse, Greensburg, Pa. and Philadelphia. And the poems are located in time between the first Portuguese incursions into Africa and waiting, about two years ago, for my partner Naomi to come home from work. In writing about moments along this continuum, I was drawn to the presence of history in the daily and of the daily in history.

I never thought of the poems as a cohesive manuscript–I aimed for “best words, best order”–but was surprised to see themes emerge from my preoccupations of the past several years: race mixing, death, and marriage.

Tell us about yourself as a writer. How does a poem come to you?

Tell us about yourself as a writer. How does a poem come to you?

Reading or watching or listening. Eventually, some image or scrap of information kicks up an association or a memory. I’ll go back later and observe or research but most poems grow from memories, which seem to me a powerful fiction, stories created and recorded to mark time.

How do you generally arrive at a poem’s form? Does it come to you early in your writing process that a poem would like to be written, for example, in tercets? Or do those decisions come into play later in your process? How do things unfold?

Form is a matter of trial and error for me. On rare occasions I’ve arrived at the form of the poem in the first draft. But mostly I tinker, break and reform lines and stanzas, read the poem aloud, then start tinkering over again. To be honest, I still haven’t quite figured out when a poem is done — I understand why Whitman revised Leaves of Grass throughout his life.

Music appears in “Rattla cain’t hold me” … does it appear in other work? If so, could you talk a little about the role of music in your poems?

Yeah, there’s music in several poems: Nina Simone, Mingus, Jackie Mac, Lil Johnson, the Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson II, James Brown. And certainly early ‘90s hip-hop and Dylan were models when I first sat down to write. Music usually serves as one of those aforementioned triggers to memory, so it’s often a starting point for a meditation on the part of my speakers. Also–and I’m not sure this comes through explicitly in the poems–I’m interested in music as a survival technique: slaves upending a kettle and creating not only an instrument, but a connection to their homeplace that helped them (and us) endure.

In “Port of Origin: Lancaster,” you write of a speaker who knows of his “black mother’s blood” as well as his “white father’s city.” Is this speaker twice exiled, so to speak? How does your speaker grapple with his hybrid identity (if that’s an accurate description)? In the “The Recessive Gene,” for example, we see him attempt to “scrape” his way to a new complexion.

Someone once called me a “hybrid” at a party. Made me proud to have such an obviously small carbon footprint, but the intent was likely to package me into the de rigueur post-colonial theory of the moment. I’ll leave to the critics any thoughts about the Calibanic nature of my speakers. I’m hoping that in the poems about mixed-race identity that mixed-race folks see some of their own experience in the poems, and that other folks find a reflection of any doubleness in their own identity.

Tell us a little about the inspiration for your poem, “Hart Crane as Jim Crow,” which begins with these opening stanzas.

I was wrong. You weren’t a madman,

just a minstrel without burnt cork

or the courage to steal chickens.

At the East River, eyeing the barely

men who reminded you of Ohio

before the fall, you finally understood

the acetylene burn of progress,

the elemental rupture of the age,

inferno lit on fuse of pure air.

On first read I had a difficult time finding a point of entry into The Bridge until I arrived at the poem “The River” and the section that reads, “under the new playbill ripped / in the guaranteed corner — see Bert Williams what? / Minstrels when you steal a chicken just / save me the wing.” Understanding that the speaker of this poem identified with a minstrel performing in black face helped me appreciate the grotesquely performative nature of the poems in the The Bridge and of Crane’s own biography. If we get right down to it, all speakers in all poems serve as masks but after the Bert Williams line here, this masking has seemed to me especially acute in Crane’s work. Ultimately, as with most modernist poems I’ve read, I’m put off by devices in Crane’s oeuvre that I perceive as creating emotional and epistemological distance between the poem and the reader–I guess this makes me appreciate the peek behind the mask all the more.

♦

“When a poet takes me to the point of discomfort, I want to know through the accuracy and power of his language that he has done so thoughtfully and responsibly.”

♦

What are your thoughts on the discussions raging in writing communities and beyond about Claudia Rankine’s recent comments on Tony Hoagland’s controversial poem, “The Change”?

I should say that I’ve met and admire Claudia Rankine, and only know Tony Hoagland through his literary biography and the handful of his poems that I’ve read. With that caveat in place, I find the Hoagland poem in question, “The Change,” problematic, and I think it was fair of Rankine to challenge the poem, especially in such a poetic and thoughtful fashion.

I understand that Hoagland designed the poem to explore a difficult topic in a way that caused discomfort–being a gadfly seems a worthy intention for a poet. I also understand that Hoagland is not the speaker but has purposefully created a speaker who expresses a line of thinking held by some but not usually expressed publicly. In my reading, the poem mingles racial and sexual politics: a White male speaker worries about domination at the hands of a Black female subject. The speaker seems uncomfortable with female sexuality, and in the line, “The young girls show the latest crop of tummies,” he comes across as Victorian. The speaker seems attracted to the White tennis player because she can be controlled–the “European” tennis player has “thin lips” and is described as “little.” However, in the speaker’s description the Black tennis player is out of control and her sexuality dangerous. The extent of her size and darkness appears to overwhelm the speaker because he calls her “big” and “black” twice; her hair is “complicated”; she wears “bangles” to a polite tennis match; her name is unfamiliar–if not unpronounceable–to the speaker, as “Vondella Aphrodite” is clearly a caricature of her name; she’s “unintimidated”; and in victory she holds her racket “like a guitar,” an instrument of love that the Moors introduced to Europe. The “you” in the poem has no clear markers of identity, but given the notes of sexuality in the poem, I read the “you” as a beloved. The beloved cheers for “Vondella” and so I wonder if the speaker worries about his lover’s sexuality overpowering him, growing out of his control, and ultimately changing the dynamic of their relationship “when [they] put it back where it belonged.”

But it’s not this tack that I find problematic–poems expressing a man’s worries over the shifting balance of power in a romantic relationship or expressing a white man’s fear of being dominated by a black woman’s sexuality in changing times could be troubling but powerful if handled correctly. By that’s the rub: I don’t think the poet handles this content correctly. The line “I don’t watch all that much Masterpiece Theatre” seems slack in its attempt to be conversational. Couldn’t the immediacy of history and the sometimes blinding nature of sight be better expressed than in the cliché, “Right before our eyes”? And “Poof, remember?” seems hackneyed. When a poet takes me to the point of discomfort, I want to know through the accuracy and power of his language that he has done so thoughtfully and responsibly. Hoagland’s word choices and line integrity don’t inspire trust, and as a result I think he leaves himself open to charges of being ignorant, sexist, and racist.

While we can understand the flooding in “Chorus of X, the Rescuers’ Mark” (LISTEN: MP3 audio) as a kind of allegorical or metaphorical flooding, it’s hard not to recall images of Hurricane Katrina’s devastation while reading this poem. Tell us a bit about both the inspiration for the form and how the poem’s use of the repeated “say” came about.

Inspiration for the poem and its form came from a trip to New Orleans several years after Katrina. Pre-Katrina, I’d visited New Orleans three times, once on a college road trip and twice to visit a friend who landed a teaching job in the city. I was not prepared for the still rampant devastation, the abandoned and unrepaired houses with roofs sheared off like the half-opened tops to tin cans that I saw on the way to help with the Habitat for Humanity project at Musicians’ Village. I was also struck by circled Xs spray-painted on many of the houses, which turned out to be the marks left after search parties had checked houses in the wake of Katrina. When I researched these marks, I saw them suggesting narratives. In turn, the collection of narrative voices led me to a chorus, as in both Greek chorus and gospel choir. In terms of form, I think of the anaphora of “X say” as a choral voice and the narratives that follow as individual voices from the chorus. And you’re right–not all of the narrative snippets developed from stories of Katrina. Some developed from family history, from floods that ravaged Southern Tier New York and Upstate Pennsylvania in 2006, from the flooding narratives of Blues music.

The repeated “say” came from the tinkering process I described earlier. I started with “mark” but “X mark” was the diction of piracy and buried treasure. I experimented with other verbs but when I tried “say” the long “a” had an elegiac sound that I thought fit the tone of the poem. I left the verb as a plural verb to hint at the vernacular, Blues tradition of songs about floods but also to leave open the possibility that X could be read as a plural, collective noun.

Thanks for the questions, Ruba! Appreciate the chance to talk about poetry, process, and the book.

*I have seen Iain do this.

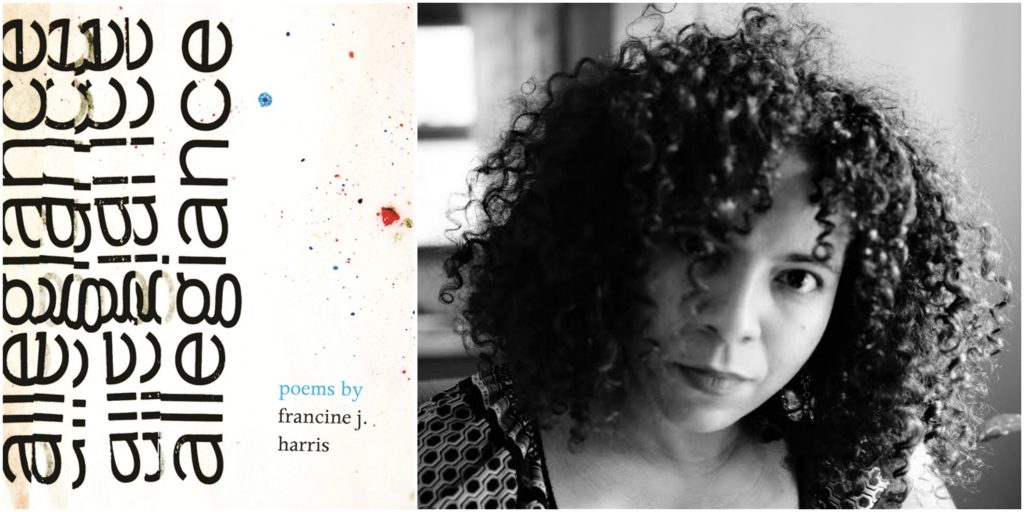

Photo: Rachel Eliza Griffiths