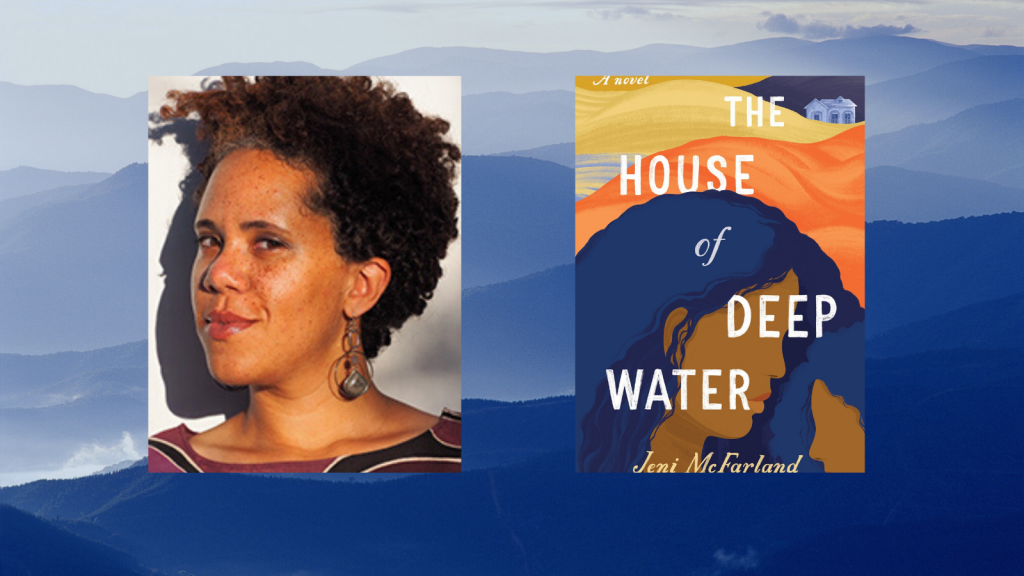

Jeni McFarland holds an MFA in Fiction from the University of Houston, where she was a fiction editor at Gulf Coast Magazine. She’s an alum of Tin House, a 2016 Kimbilio Fellow, and has had short fiction published in Crack the Spine, Forge, and Spry. She has been nominated for the storySouth Million Writers Award. She was also a finalist for the 2015 Gertrude Stein Writers Award in Fiction from the Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review. She has lived in Michigan and the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband and two cats. The House of Deep Water is her first book.

In The House of Deep Water (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, April 2020), three women return to the fictional town of River Bend, Michigan. In light of Paula’s history of neglect, Linda and her sisters want their mother to stay gone. Linda leaves her marriage, only to move in with the town’s aging bachelor. When Beth returns to her father’s house, she finds the younger Linda an unwelcome presence. Theirs are reluctant homecomings and tense receptions that coincide with the televised trial of a man whose terrible crimes haunt the town.

Through its examination of parenthood, race, and desire, The House of Deep Water confronts the impact of cultural silence on everyday lives.

Elinam Agbo (EA): The theme of leaving is quite central to the novel, and several characters have a push/pull relationship to the town and members of their family. Boundaries and claims to place are fundamental to this dynamic. Would you say the outsider/insider binary is unavoidable in narratives of small-town America? In the case of River Bend, why do think this may be the case?

Jeni McFarland (JM): I can’t speak to all small towns, but the one where I grew up, the insider/outsider binary was especially obvious. Kids who moved to town in high school, who didn’t grow up with everyone else since preschool, were hard-pressed to find an “in”—unless they were star athletes, of course. River Bend is like that, in part because everyone has their place, and in a town that’s happy to stay the same, there aren’t new places created for new people to fit.

EA: I’m very interested in that idea of a place “staying the same.” It is very striking when Beth’s children point out to her that Black people were also present in River Bend’s history and that they’d been erased in the Gaslight Village museum exhibit. What did it mean for you to let Beth’s children, who are comparatively “outsiders,” educate their mother in this way?

JM: Sometimes I think it takes an “outsider” to really see things clearly. For Dan and Jeanette, they don’t know the town like Beth does, they just know what they’re learning in school—and, of course, they’re smart and can read between the lines. For Beth, she doesn’t know the town’s official history like Dan and Jeanette do. Their generation is the one that’s taking a deep look at history, seeing the patterns, and then stepping up to address social issues in ways Americans haven’t in a long while. And of course, history changes, or at least our official version of history does, as we become more self-aware as a society. It feels trite to say the children are our future, but if our future holds enough kids like Beth’s kids, I think we’re going to be alright.

EA: Water is a powerful motif throughout the book, especially in relation to Beth’s duality. One of my favorite scenes is the moment Eliza first surfaces from the depths of Beth, and I started to read Elizabeth DeWitt’s doubling as her coping mechanism: Beth as the “rage,” and Eliza as the “complaint” one who can hide her turmoil to make others more comfortable. How did you arrive at the motif of water as a way to access what remains unsaid in Beth (and River Bend)?

JM: The motif grew organically out of the text. There was a line that existed even in early drafts, when Beth first arrives in River Bend, and she doesn’t want to get out of the car. She sees her father hug her daughter, and the line is “something inside Beth stirs violently, and she spills out of the driver’s seat and onto the driveway.” I liked this metaphor and wanted to see how far I could push it, so I started thinking about what it was that stirred in Beth, and where all that water came from.

EA: Beth’s relationship to her father is so complex and layered. In the chapter about the Gaslight Village exhibit, the boys call twelve-year-old Beth the n-word, and her father’s reply to her complaint is “Sticks and stones.” This hits hard, and yet the placement of each of these moments is meticulous, allowing us to experience the town’s perspective, slowly making our way inside their houses, and then inside each person. The result is the immensity of Beth’s isolation: not only as a Black person in a predominantly white town, but also as a sexual assault survivor. Can you talk about navigating the psychology of characters when there are such loud silences? Was there ever a time in the writing process when Gilmer Thurber’s crimes threatened to overwhelm the other conflicts?

I think that in maybe the draft I first sent my editor, Thurber’s crimes did overwhelm. She really helped me take them back a step and realize I didn’t need to show too much.

As for the psychology of writing silences, I’m very interested in the things people don’t say. There’s a culture in the Midwest, where I’m from, that we don’t talk about things that are unpleasant, which creates a real taboo around them. As a sexual assault survivor, that taboo feels like guilt, like the things I’ve experienced aren’t the problem, but the fact that I want or need to talk about them is. I really want to break down those taboos, because I know I’m not alone, and that talking helps. Silence is really the language of perpetrators; they tell victims, especially young children, not to say anything or else. I for one am done with silence.

EA: Let’s return to the children. The teenagers. It is very powerful how Beth’s children navigate their mother’s rage and remain sympathetic even when they don’t know the whole story. Often, Dan and Jeanette seem older than they are in how they handle familial tensions, and yet we know they aren’t okay either. Can you speak to the experience of writing young people who have to grow up quickly?

JM: I think what these teens deal with, in the moment for them, it just seems like life. They’re not really aware that they’re growing up quickly, or dealing with anything out of the ordinary. It won’t be until they’re older, looking back at their lives, that they realize there was anything amiss.

EA: Animals also play a key role in major moments of characterization. You think you know Steve (though does anyone know Steve?), and then you meet his African parrot. You think you know Paula, and then she delivers the Jesus cow, unflinching while the men are close to throwing up. Do you enjoy writing animals? Do you consider them more characters or setting?

JM: I love writing animals, but then I’m a huge animal lover. I swear I know what my cats are saying to me most of the time (and let me tell you, they have filthy mouths!) and I very much enjoy speculating what other cats and dogs are thinking. They’re definitely a character for me, as their actions can complicate a scene and add an element of chaos.

EA: With the structure of the novel—multiple POVs from different characters, the consistency of Eliza’s vignettes, the men’s occasional (but very eye-opening) voices—you establish a town with very clear dynamics and a firm presence. How did you decide which narratives were central? Which characters came first, and who arrived later?

JM: Again, my editor helped me with this. There were earlier drafts with other POV characters that were later cut—Skyla, Paige, and Hannah were the ones I was most attached to. And the chapters from Greg and Steve were added later, to help round out the narrative. I felt like it was important to see the town from multiple perspectives, mostly because I did draw so heavily from my memories of the town where I grew up, but I also know my memories are skewed because being a teenager is terribly rough. Add to that undiagnosed depression, and I knew my own perception wouldn’t do any town justice. I needed to see it through other eyes too.

EA: What are you reading now? And are there any coping strategies you’d like to share?

JM: I just finished reading A. Rafael Johnson’s novel The Through, and holy wow! It was so poignant and heartfelt and truly original; I can’t praise this book enough. I’m sort of taking a break from novels now though and reading all the free stories I can find online.

As for coping strategies, I don’t even know. I tried the baking bread strategy and gained a lot of weight. Now I’m trying the home improvement strategy. I’m painting my kitchen cabinets, which, let me tell you, is a surprising amount of work. Not the painting itself, I like that, but the disassembling of the cabinets. I feel like I’m on a home renovation show! The end product is going to be worth it, though.