Recently, while home for the holidays, I was catching up with some friends from high school when a particular Young Adult series that my friends read came up. It wasn’t a series I had heard of, but the name alone tipped me off of the genre, as well as the subjects my friends were discussing. When I asked what she liked to read about, my friend shrugged and offered that she liked stories with ghosts, that she enjoyed reading about young people and that she didn’t like books that took themselves too seriously. I suggested she read some Kelly Link.

I realize now that I owe her an apology.

At first, I walked away from the conversation believing that I had done a good thing. I was turning one of my friends on to literary fiction, maybe drawing a new reader to a genre that often bemoans its dwindling audience. Link could be a great gateway: a writer who masterfully implements elements of science fiction, fantasy, even a little bit of YA.

But was it not a little bit condescending to imply that now she could graduate from her silly little YA to Kelly Link?

(But, seriously, Kelly Link is great. Please read this Kelly Link story if you get a chance. Or this one. Or both, just saying.)

There has always been a tension between literary fiction and young adult fiction, or other genres of “popular” fiction. Readers and writers of the former dismiss the latter as frivolous, manufactured and artless. When speaking of her award-winning novel A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, a book lauded by The New York Times as a “future classic,” author Eimear McBride told The Guardian: “I think the publishing industry is perpetuating this myth that readers like a very passive experience, that all they want is a beach novel. I don’t think that’s true…. There are serious readers who want to be challenged, who want to be offered something else, who don’t mind being asked to work a little bit to get there.” I’ll admit three things: (1) I am only about halfway through A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, (2) it is thus far worthy of its acclaim, and (3) it is incredibly challenging. And of course it is: McBride was inspired by James Joyce when writing it.

While the commercial success of A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing is encouraging, the way discourse around the book often frames it against popular fiction is curious. The Only Way is Reading’s review even framed the A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing as the “bare-knuckled fistfight” in the face of modern fiction’s “Marquis-of-Queensbury-ruled boxing,” taking it one step further to say that the novel is “the savage and fucking hard-hitting end of the genre.” Reviewers are not only fascinated with the idea of literary fiction being at odds with popular fiction, they’re excited by the prospect of a bloody, street-brawl-style takedown.

What’s more, the process of publishing A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, a decade-long endeavor of rejection after rejection, is romanticized in interviews and reviews. Once again, we see the book framed within the context of struggle against the publishing industry. But it’s strange that when posing A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing against popular fiction, no reviewer has stopped to consider the book as a work of YA. The novel follows a young woman’s coming-of-age tale, through an adolescence plagued by illness, abuse and trauma. If we are to understand young adult fiction as literature that describes the experiences of young people, why should McBride’s work be lauded as the destructor of others like it? Because it’s more difficult to read? Because it’s grittier?

It’s hard to respect the accusations of YA being fluffy and literary fiction being brutal and honest when both genres coexist on this spectrum, if this is even a true dichotomy. Kelly Link talks about girlhood in reference to ghost boyfriends and GIFs of penises on Tumblr in prose that is simple and clean, while Eimear McBride paints the same burgeoning teenaged sexuality in much darker strokes through an involved, difficult stream of consciousness. Both are considered literary. And it is not as if YA doesn’t get dark. I’m reminded of Sherman Alexie’s powerful Wall Street Journal article “Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood,” his response to Meghan Cox Gurdon’s complaints that YA was becoming too dark and explicit. Alexie, a young adult author and abuse survivor, felt compelled to defend YA’s grittiness by countering: “As a child, I read because books–violent and not, blasphemous and not, terrifying and not–were the most loving and trustworthy things in my life. I read widely, and loved plenty of the classics so, yes, I recognized the domestic terrors faced by Louisa May Alcott’s March sisters. But I became the kid chased by werewolves, vampires, and evil clowns in Stephen King’s books. I read books about monsters and monstrous things, often written with monstrous language, because they taught me how to battle the real monsters in my life.”

So if YA is just as honest as literary fiction, where does our distaste for it come from? There is the argument that–with its tendency for serializing its stories to send the same sets of characters quick, neat adventures–YA looks a lot like television. And we all know how literary fiction usually feels about television. Take David Foster Wallace, who explained in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, “I’m not saying that television is vulgar and dumb because the people who compose the Audience are vulgar and dumb. Television is the way it is simply because people tend to be extremely similar in their vulgar and prurient and dumb interests.” (Thanks, Dave.)

Vulgar and prurient and dumb. They’re the sort of adjectives we not only often ascribe to young adult fiction, but to teenaged girls, who are overwhelmingly the protagonists of young adult fiction. It’s no surprise that culture dismisses the interests of this demographic before co-opting them. Just think about The Beatles, whose legacy now seems preserved by middle-aged men who dismiss the same population that catapulted the band to success, teenaged girls, as tasteless and frivolous. It could be my own internalized misogyny that prevents me from taking these stories seriously at first glance. When literary fiction still struggles to write women without the same invisible hand of misogyny, I’m excited to see the world of YA allows women to be heads of armies, political leaders and general badasses.

I’m reminded of the scene in 30 Rock where Liz Lemon is anxious about attending her high school reunion for fear of encountering the “cool kids” and being bullied, only to discover that she was the bully the entire time. It seems that pushing down YA, making the fight analogies, calling it vulgar, is the same kind of Liz Lemon defense mechanism. The more we make literary fiction seem exclusive, the more we put it at odds with popular fiction, the less appealing it looks.

So, I’m sorry, friends who read YA. You don’t need to graduate to Kelly Link or Eimear McBride. In a world where 42% of college graduates never read another book after college, I’m genuinely glad you’re reading something.

I leave you with Matthew Burnside’s guide for reading across genres from the Ploughshares Blog, and my sincerest apologies. My bad, guys.

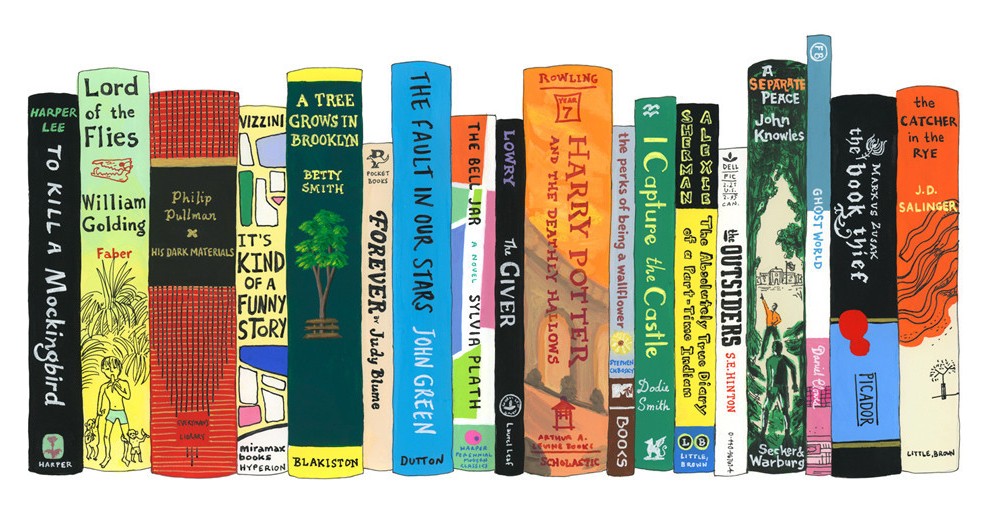

Image: “Coming of Age” from idealbookshelf.com.