In his manifesto Reality Hunger, David Shields uses assemblage to curate a dialogue about the limits of The Real. The voices he appropriates and sequences implicitly argue that our increasingly urgent twenty-first century desire for reality is compromised by the fact that our storytelling mechanisms are growing further from it. As Shields notes (without acknowledging in the text proper that he is parroting E. L. Doctorow), “There’s no longer any such thing as fiction or nonfiction; there’s only narrative.”

I am interested in prose that works as narrative, that lives in the clefts between fiction and nonfiction, between work that creates and work that critiques. I am interested in writing that does not construct character or story-world, nor attempt to re-construct a past; rather, I am drawn to writing that exposes all narrative’s instability by confessing its own failure, work that foregrounds its own artifice, work that from its beginning is already performing dénouement, that word that translates from French to English as untying.

Lydia Davis’s short story “Happiest Moment” does just that. I’m reproducing the whole piece below:

If you ask her what is a favorite story she has written, she will hesitate for a long time and then say it may be this story that she read in a book once: an English language teacher in China asked his Chinese student to say what was the happiest moment in his life. The student hesitated for a long time. At last he smiled with embarrassment and said that his wife had once gone to Beijing and eaten duck there, and she often told him about it, and he would have to say that the happiest moment of his life was her trip and the eating of the duck.

This story haunts me—and I mean that in the best way—because it first summarizes and then complicates every question we might pose about prose. It asks what it means to own a story, and how narratives are circulated. It raises questions about where the self ends and it exposes the act of storytelling as our primary means of instituting order on the tumult, fracture, and plurality of lived experience. It outs itself as text.

Davis has long been cited as a writer working at the intersections of genres—is her work fiction or essay, allegory or anecdote, story or philosophy?—but what I find transformative about this short piece is its eerie self-consciousness, its ability to execute a paradox, riddle-like, that is at once speculative and retrospective, that is both a compact work of literary art but also rises off the page toward three-dimensionality. In this way, it is neither fiction nor nonfiction—it is narrative performed to its exhaustion, that uses the tenets of writing to fold back against itself, that makes obvious and evident the uncanny nature of the reading act. It is fiction that both abides by the rules and rejects them, simultaneously. Another word for this might be theory.

But “Happiest Moment” also, covertly, performs. It was after years of writing about and reading through and teaching around this piece that I started to grow curious about whether “the story” mentioned is one that only she-our-narrator “read in a book once” or if Davis-our-implied-author did, as well. After some light online research, the answer was revealed: “the book” is Mark Salzman’s 1986 memoir Iron and Silk. A quick look at pages 57–58 reveal a scene in which Salzman, then a teacher in China, asks his students to write about their happiest moment. When one student shares his narrative of eating duck in Beijing and is subsequently praised, the student immediately falls into a veiled form of confession: “Teacher Mark. I have to tell you something. Actually this story is true but actually I have never been to Beijing. Can you guess? My wife went to Beijing and had this duck. But she often tells me about it again and again, and I think, even though I was not there, it is my happiest moment.”

This is how Davis’ piece becomes locked in a kaleidoscope of telling: the story is a narrative appropriated by a husband from his wife, borrowed by an essayist as a scene in his book, re-authored by Davis who owns it only speculatively, only “if you ask her.”

I read “Happiest Moment” as an interrogation of the art of telling. It is one bit of evidence suggesting there is merit to Doctorow’s claim that “There’s no longer any such thing as fiction or nonfiction; there’s only narrative.” Davis’s piece is narrative about the very fact that there is only narrative.

And so, perhaps we should not be thinking about prose as a field designated by truth factor, for—as “Happiest Moment” suggests—it is a vein effort to track the trace that is story. Instead, the question that good prose raises (whether fiction or its slippery non-) is the question of every story’s requisite relationship with narration, of who is delivering our narrative and how that delivery is shaping the tale we receive. Davis seems to argue here that the question we should be asking of prose is not whether the story is true and how closely the truth has been followed; rather, the better question—the question at the root of the truth factor of any text—is this: who delivers our stories and how is that delivery always already manipulated by the speaker’s mind and mouth?

We need stories, of course, but we also need to be aware of how those stories are framed. We need to adopt a healthy suspicion about the stories we receive. We need stories, of course, but we also very much need the power to reject them in service of listening to another narrator, one who tells differently, perhaps better. As Beth Loffreda and Claudia Rankine note in their introduction to The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race and the Life of the Mind, “The universal is a fantasy.” I wonder if we sometimes forget this, forget that the common reader is a myth, forget that the history of the word art is bound to that of the word artifice.

And it is that artifice that we must crack open and apart to uncover and disclose some kind of reality. For in the end, our work as consumers of any narrative is to recognize and question the façade the narrator uses to make her claims.

Or, as James Baldwin puts it: “The purpose of art is to lay bare the questions hidden by the answers.”

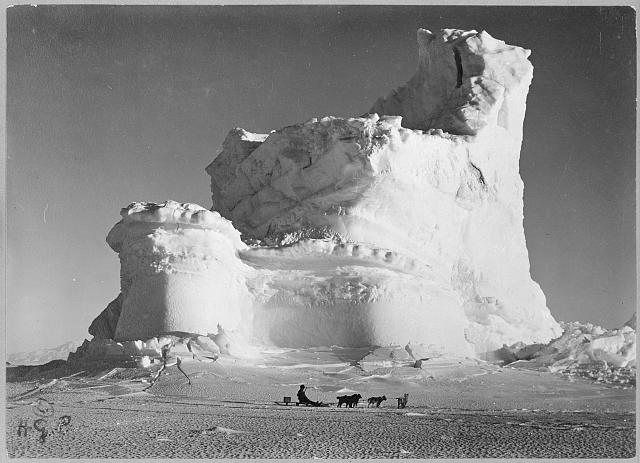

Image: “The castle berg, a weathered iceberg.” Herbert George Ponting, 1910 or 1911. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.